Aegean Tale: The Walls of Smyrna

Part 2 of a series on Old Smyrna: the town suffers during the Trojan War but later becomes a destination for Aeolian and Ionian colonists -- a curse on the city remains and will destroy the town.

To read the first installment, The Naming of Smyrna, use this link.

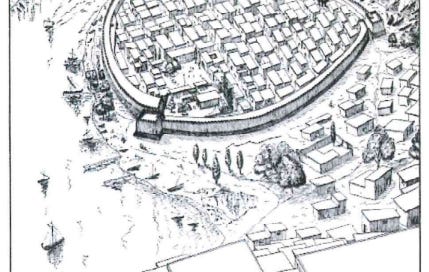

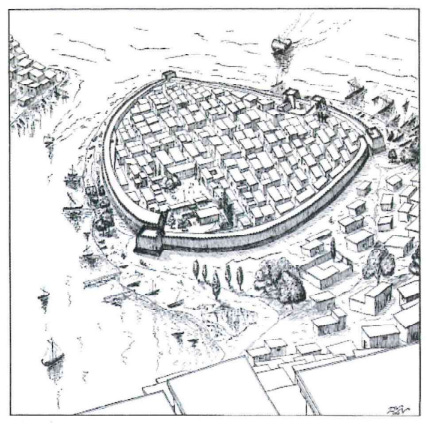

“Smyrna” was the name of an Amazon princess before it became the name of a city on the eastern coast of the Aegean Sea. Built on a cape around which the rushing River Meles collided with the salt waters of a gulf, the city was destined for conflict.

At the naming of the city, two gods vied to be Smyrna’s patron and namesake: the sea god, Poseidon, and the river god, Meles. When the Amazon princess became the namesake instead, the two gods vowed to destroy the city, each in their own way.

Smyrna lay under a curse.

The Sack of Smyrna

In the decades after Smyrna’s founding, the Amazons gradually drew back from the coast or left their tribe to marry among the Leleg inhabitants as Princess Smyrna had done. Surrounded on three sides by water, the community still struggled to find adequate defences. They erected a watchtower on top of the bluff and stationed three watches throughout the day. Still, seaborne raiders would sail into the gulf and attack the city — or nomads would raid from their mountain hideouts.

One of the worst attacks came during a nine-year-long siege of the city of Troy, about 300 km north of Smyrna, where an alliance of Greek chiefs had besieged the city.

One of those Greek chiefs, a warrior named Achilles, regularly left the siege to lead seaborn raids on cities southward along the Aegean Coast all the way to Ephesus. He returned to his Trojan base after every foray with shiploads of plunder and slaves, enriching his allies while weakening the coastal cities who might support his Trojan enemies with soldiers and supplies.

One day he sailed with five ships into the bay and launched a surprise attack on Smyrna. Three of the ships landed on the beach and engaged the Smyrnaean militia. Meanwhile two ships snuck into a nearby lagoon and launched a land attack from the north. The land force overwhelmed the city, killing most of its defenders and dragging many women and children back to Troy.

It would take one hundred years before Smyrna’s population recovered – and the legacy of this deadly warrior would pass down more than 300 years before a man from Smyrna, Homeros, would compile accounts of Achilles’ exploits into the book known to us as The Iliad. But that is a story for another time.

Colonists from Greece

Four generations after the sack of Smyrna, a group of men arrived from the north. They carried no spears. Instead they pushed carts bearing their belongings, showing that they intended to stay. They spoke a strange language – the Smyrneans of that time would not have known, but these newcomers spoke Greek, just as Achilles had done. In fact many of these colonists came from Thessaly, the homeland of Achilles, which had suffered famine and military setbacks in the century following the Trojan War.

The men called themselves Aeolians, and they had come from a city to the north called Kyme, a “mother city” or metropolis for migrants who had traveled from the other side of the sea. The Aeolians settled among the Smyrneans, built farms, developed trade – many of them even married Leleg women and established families.

This migration marked a turning point for the community. It grew rapidly. It soon had a population of 2,000. The grandchildren and great-grandchildren of these Aeolian migrants became leaders of Smyrna and formed a loose alliance of Aeolian city-states stretching northwards from Smyrna along the eastern shore of the Aegean – all the way to the Hellespont. The trade links between these city-states brought more ships into the gulf. Smyrna became a wealthy city. It had allies among the other city-states in the “Aeolian League,” but it still needed a wall to protect it from pirates and raiders.

The First Wall, 850 - 700 BCE

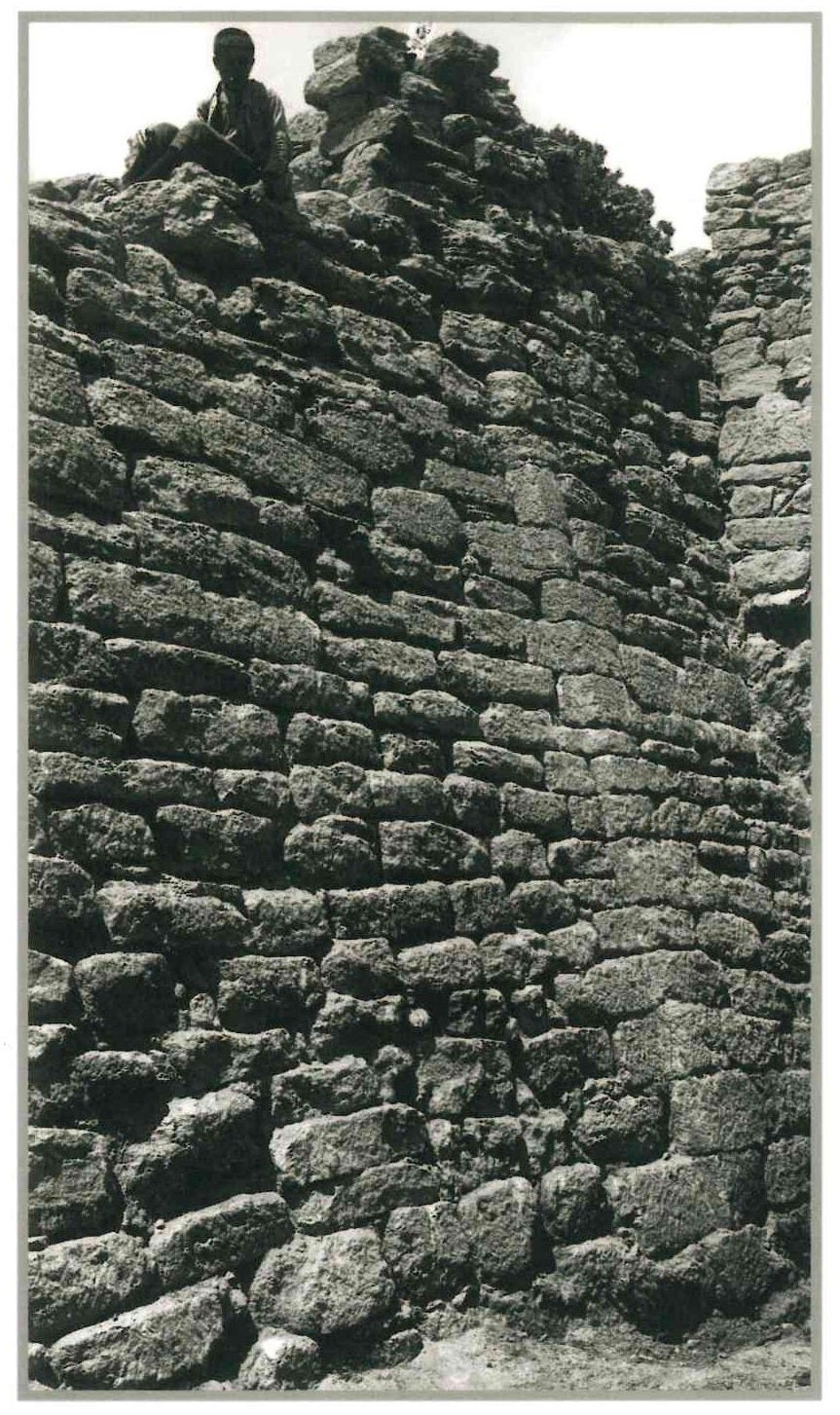

The Aeolians built the first wall of Smyrna.

With the city surrounded on three sides by water, they focused on the northern end of the city, which led out to the base of the cape, from which Achilles’ attack had come —the logical route for a land invasion. There they fortified the old watchtower with red, andesite stone – a type of limestone found along the slopes of Mount Yamanlar. They wouldn’t stop with a tower. Smyrna needed walls to protect everyone.

Walls had been a common defense for centuries, but the walls had always surrounded a palace complex, protecting the ruling family but leaving the civilization at risk. Smyrna would enclose the whole city – and once it did, it would become the first city in the Greek-speaking world to have such a wall.

Builders laid out foundations, which began at the all-important northern side. A narrow gate entered the city behind the fortified tower, continuing into the city with walls on either side for about 15 meters.

Above the foundation, builders raised a wall made of stacked mud bricks, which rose at steep angles to a height of 2 meters. Facing stones covered the mud bricks, preventing their erosion by wind and rain.

The dimensions of the new wall matched the shape of the cape upon which the city rested: a triangle with its sides curved slightly outward. The 5-meter-wide Bay Wall reached westward along the shore to the tip of the cape where the Meles River entered the bay. It had a gate in the middle to allow access to merchants whose ships pulled up onto the beach.

From the tip of the cape, a second wall ran towards the northeast, parallel to the river. This River Wall also faced the harbor and had a wide double gate guarded by another tower that overlooked the harbor.

The third wall was the most important, as it faced the land bridge at the base of the cape. The Land Wall stretched northwestward from the harbor gate to the guard tower, with a gate at the northern end, near the tower.

One defensive feature that Smryna lacked was a hill or acropolis on which to build a fort. Behind the Land Wall, the Smyrneans erected a broad, flat mound that cleared the height of the outer wall. On this platform lay a courtyard for military training and a height from which to rain arrows and stones on invaders.

The wall enclosed the entire city. People came from other cities and across the sea to see the walls of Smyrna. Within the walls, Smyrna’s houses were oval dwellings, scattered along curved streets among the walls.

Smyrna still lay between the river and the sea. It was now protected by a wall, but the curse had not lifted. Flamingos remained in the lagoons around the city, reminding the residents of Poseidon’s gift at the city’s founding, and the river spring still flowed. The gods’ bitterness remained, however.

Several times the river god, Meles, flooded the harbor with mud and fallen trees, leading to months of work removing the tangled limbs from the water and clearing a path to the harbor. Poseidon shook the earth regularly, and a part of the Bay Wall once collapsed and had to be repaired.

The gods weren’t the only ones vying for the beautiful city of Smyrna. A league of cities to the south, the Ionians, competed with the Aeolians in trade as well as to attract settlers. Smyrna lay on the border between two leagues of city-states.

A group of refugees from the Ionian city of Colophon came to Smyrna and asked to live there. They had lost a civil conflict and were no longer welcome in Ionia.

The Smyrneans, happy to add new settlers, ignored the Colophonians’ squabbles and welcomed them to the city.

That winter, around the time of the solstice, the citizens of Smyrna paraded out of the city and spent three days at a temple on the slopes of Mount Yamanlar, celebrating the festival of Dionysus with singing, dancing, and wine parties.

When they returned to their city, the gates were locked. The Colophonian refugees appeared atop the wall and declared, “Smyrna is an Ionian city now.”

Help came from other cities in Aeolia, but they could neither breach the walls nor drive out the Ionian usurpers. Finally, the two sides negotiated a truce.

The Aeolians of Smyrna were allowed to enter the city to remove everything they owned and take it to new homes elsewhere in Aeolia. The Ionians kept the walls and everything within them that couldn’t be carted away. Smyrna became the 12th and final member of the Ionian League. The number of Aeolian cities fell from 12 to 11.

Wall II 700 - 610 BCE

The Ionians would build a new wall, greater than the one the Aeolians had built.

The second wall required a broader footprint and a foundation of stone. The new wall changed its course around the south and west of the city to accommodate a larger population, all asking to be enclosed within the wall.

The eastern bend of the wall now passed along the slope where Meles’ spring still flowed. There was no way to go around it: building the wall below the spring put it on the flood plain of the river, and houses already lay above the spring, needing protection.

The engineers came up with a clever solution: they built the wall over the spring. This is not to say that they filled in the spring that the river god had given. Instead they added an alcove into the wall, which shaded the spring. There was now an huge, double-winged gate that opened to the harbor and a narrow, single-door, “false” gate about 100 meters south that led to the spring.

The engineers widened the base of the Second Wall, which ranged in width from two to four meters. It was twice as high as the first wall. As a finishing touch, the surface of the baked-brick walls were covered with a smooth coating of mud and a fresh coat of paint, creating a beautiful, adobe wall around the growing city-state that gleamed beside the bay like an Aegean pearl.

Poseidon was displeased. He had promised Meles that he would destroy the city.

He did.

He struck the cape with an earthquake. The entire city shook for 30 minutes, with forty more aftershocks in the following weeks. By the time the ground stopped shaking, the entire wall had collapsed. The adobe bricks had cracked and disintegrated. Smyrna lay in ruins.

For a month after the ground stopped shaking, the people of Smyrna remained camped outside their ruined city, nursing the injured, praying to an array of gods for relief from suffering. From atop Mount Mimas at the western end of the bay, Poseidon watched the Smyrneans to see where they would go, now that their city was destroyed.

A ship arrived from Mytilene, a city on the island of Lesbos. They unloaded supplies for the earthquake-stricken citizens. There were also a group of builders among them, and they met with the city leaders of Smyrna and walked two circuits around the ruined walls, carefully noting the foundations and the condition of the mud bricks. These men conferred for two days; late on the second day, they emerged with a plan for a new city.

As the sun set over Mount Mimas on the second day of the Lesbians’ visit, a tiny, orange arc gleamed above the mountain. Poseidon left the bay and dove into the Aegean. He had done what he had promised: he had destroyed the city. He would leave the bay forever; he couldn’t bear to watch Smyrna restored.

The Smyrneans would rebuild. This time, they would design a wall of earthquake-proof stone!

Much of the information for this series comes from scholarship related to the archaeological site of Old Smyrna/ Bayrakli Mound. This story has been months in the making, as I tried to make sense of the site’s vast history.

That’s why I’m telling the story of the city’s walls. They illustrated the forces that shaped Smyrna: natural, Leleg, Aeolian, Ionian and — as I will relate in the next installment of the story — Lydian, Persian, and Macedonian.

Other tales in this series:

The Naming of Smyrna — from prehistory to the Bronze Age.