Asian Spring and Ancient Traditions

The spring festival of Nawruz unites cultures from Izmir to Samarkand

It is holiday time in Turkey, and there are many to choose from.

Since mid-February Christians have been in the lenten fast, which began after Fat Tuesday and will close at the end of this Holy Week on Easter.

Islamic Spring: Ramadan

We are now two weeks into Ramadan and just two weeks from the Bayram holiday that will celebrate the end of the Muslim season of fasting on Wednesday, April 10. I live quite close to a really large mosque, and it feels like a few more calls have been added to the daily songs by the muezzin. There was one about an hour before sunrise that awoke me this morning.

Another interesting Ramadan tradition is the drummers. They go through the streets, banging on a drum. Residents must pay to encourage them to move on. Last year, I answered a doorbell and let a couple drummers into my apartment complext, and they went floor to floor, collecting donations (including a nice one from me). I sure hope that my neighbors were in a festive mood and didn’t investigate to find out who had let the drummers in.

My school will get a week off for Bayram (known more broadly by its Arabic name, Eid al-Fitr). It is a time when Turks of all religious persuasions try to reconnect with family. I’m looking forward to my first trip to Ankara to see that city and join my girlfriend, Füsun, as she visits her family.

Ramadan follows the lunar calendar, not the solar calendar, so it doesn’t always coincide with spring celebrations. This year it does, and that is great.

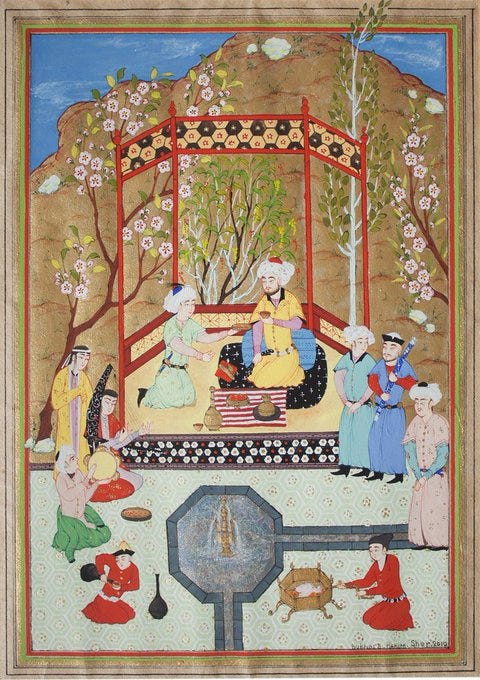

Persian New Year: Nawruz

A new holiday has captured my imagination this year. It’s the festival of Nawruz, celebrated throughout Asia many centuries before Easter or Ramadan or Passover, for that matter.

Last Thursday, March 20, was the first day of Nawruz, and my Grade 11 class, over half of which is Persian, was nearly empty. Attending school on Nawruz (or the 12 days that follow) would be for a Persian like a westerner attending school on Christmas Day or New Year’s.

Some Nawruz traditions are recognizable in the west. Prior to the festival, families engage in spring cleaning or khoone takoone. With the house all clean, on the day of the vernal equinox — calculated to the very hour the sun crosses the celestial equator — celebrants leap over fires (or lit candles) to cast the cares of the old year away and get a new start in the new year.

One of the most fascinating for me is the tradition of Haft Sin, the seven symbols of Nawruz (the name means “new day” in Farsi), all of which start with S and have special symbolism for the hopes of the new year:

Sabzeh – Sprouts of lentils or wheatgrass cultivated in a plate.

Samanu – Wheat germ is used to make a delicious pudding.

Senjed – Dried oleaster

Sir – garlic.

Sib – apple.

Sumac – a crushed spice.

Serkeh – vinegar.

The Vernal Equinox in Ancient Greece

On Palm Sunday, I drove down to Didyma with my chaplain, and while he led a service for an Anglican group there, I toured the Temple of Apollo, where an ancient Greek celebration of the spring equinox is captured in stone.

On the site, just outside the temple, I found the capital of one of the huge columns. On two opposing corners are the heads of bulls. The opposite corners hold heads of lions (their faces chipped off, onfortunately, but glorious manes on display).

The motifs also come from Persia, which ruled over western Anatolia for 220 years. The bull and the lion are ancient symbols, the lion representing the power of god, and the bull representing the power of nature.

I want to focus on two elements of bull-lion symbolism.

The lion represented the sun. It’s mane extends from its face like sunbeams. The bull represented the moon. Maybe it was animal’s horns that curved like a crescent, or that so many bulls were as black as night. Either way the battle of the lion vs the bull represented the sun against the moon, constantly circling one another in the sky, one holding power for half of the solar year before giving way in cosmic battle to the other.

On the vernal equinox, the season of night — when the moon rules the greater part of the day — comes to an end and the season of sun begins. The lion battles the bull, and it overcomes to rule the days between the vernal and autumnal equinoxes.

But there’s more to this event than the victory of Leo the Lion over Taurus the Bull.

Besides the moon, the bull was also a symbol of fertility. When the bull was killed, its seed fertilized the earth and generated springtime. The local fertility goddess of eastern Anatolia, Artemis, most famously wore a vest of dangling bull testicles as symbol of her power.

Spring has sprung.

It is time to celebrate.

And there is no place like Turkey with its vast array of religious and ancient spring traditions.