Close Reading: an Atatürk Oratorio

It was standing-room-only. I understood 1/4 of the words. I left with an indelible impression of Turks and their founding father.

If there is one thing I have tried to do in my 60 posts on Substack, it has been to utilize every power of creativity, adventure, recklessness, and literary aptitude that I have to share my understanding of the Republic of Turkey and its people with you.

The longer I’m here — the better my facility with the Turkish language — the more friends I make and the more opportunities I get to look behind the curtain and see “Turks being Turks.”

Last Sunday, November 10, I started Ataturk Commemoration Day in the back of a dolmush, sharing a moment of silence with the entire country at exactly 9:05 a.m. My commute that morning ended at an Anglican Remembrance Day service where the names were read of British boys from Izmir who died in the Great War.

That evening I attended an oratorio at the Adnan Saygun Arts Center in Göztepe that brought the day to a resounding end.

I write this, admitting that I understand only 25% of the Turkish words in a given conversation — enough to “get by” as we say. My memories of the oratorio are its symbols and images. That’s what I’ll share with you here.

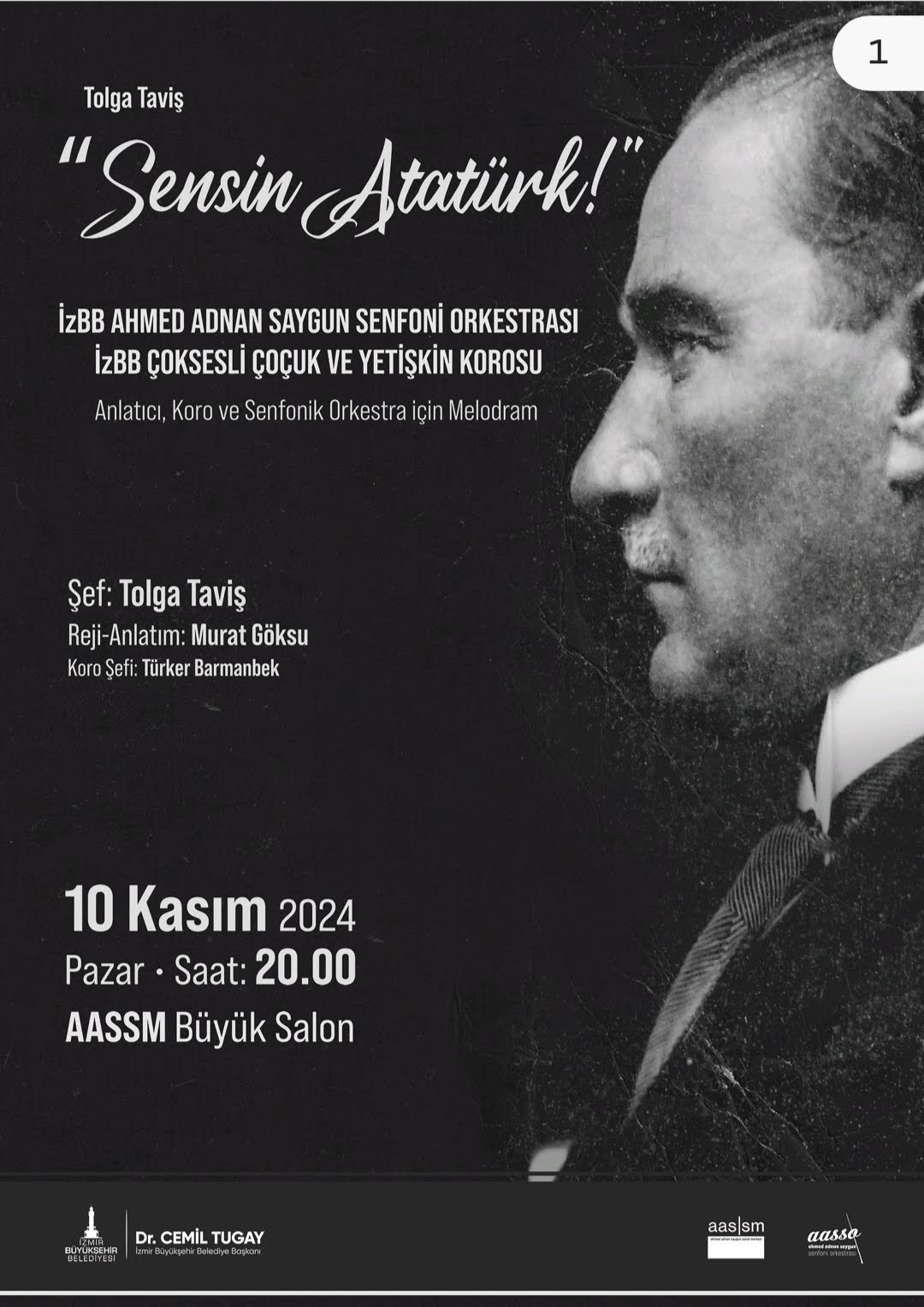

This year I joined a community choir, which has provided me with some great new friends as well as inside connections for choral events in the community. When my choir director told us about the oratorio, “Sensin Atatürk (You are Atatürk),” I added it to my schedule — only realizing later that it was on Commemoration Day.

The concert was free, so I arrived about 30 minutes early, hoping to get a seat. I knew a children’s choir was involved, and I expected an audience of aunties and grannies. Sure enough, the hall was already packed. The only available seats were already reserved.

I waited outside repeating a refrain I often repeat to myself: “Turkey is for Turks.” I didn’t need to stay — to deprive a seat to someone for whom Mustafa Kemal Atatürk is far more than an historical figure.

But as the doors were closing, I slipped back into the hall and found space to stand along the back wall of the balcony.

The orchestra began with a “taps”-like trumpet solo. Then everyone stood for the national anthem, even the members of the orchestra. I’m not used to standing for a national anthem at a theater performance. But this was a different kind of performance than any I have seen.

The Oratorio

The performance began with the chorus of about 60 members in a gyre that rotated around the center of the stage. As they turned to face the audience they held veils in front of their heads with both hands. The symbolism was clear — even if the words weren’t. Turks had ‘once been blind’ as the song goes.

There was plenty of narration in the oratorio. On Republic Day, October 29, I had walked down Istiklal Street in Istanbul, hearing a high-pitched voice coming out of speakers up and down the street. That was Atatürk, someone had explained. His voice contributed to the patriotic spirit, along with the huge, Turkish flags hanging above the street. As the oratorio moved from its opening number, the veils were wadded up and held in the hands of the chorus. As the narrator spoke, a spotlight appeared from stage right, and the chorus turned towards it. Rapt. Then the spotlight switched to stage life, and the chorus turned as well.

It reminded me of snippets of plays I had seen from the 1930s and 40s, an era of political optimism and Social Realism. Yet this was 2024. I thought of the public art that I had seen here: statues of Ataturk, yes, but also statues of happy families, dancers, shepherds herding sheep. Social realism continues in Turkey to this day, and the Commemoration of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk — frozen in time by his death in 1938, when the artform was at its most popular — keeps it alive and thriving.

But the Social Realism of the oratorio went beyond looking back and forth at stage lights. One by one important symbols of Atatürk’s message to the Turks were brought out: a hammer, encouraging the building of a new republic; a T-square for planning the next steps; the Turkish flag, and the publication of Atatürk’s famous 1927 speeches, which recollected the events from the beginning of the Turkish War of Independence to the founding of the Republic — all of which featured him in a pivotal role in a book called Nutuk.

Two primary symbols outshone the others: a girl in a red dress, red shoes and white stockings paced across the stage during two of the songs. During three more songs a chorus of about 80 children — including one in a wheelchair — came out and sang with the chorus.

The second symbol was an actor portraying Atatürk. Even from my standing-room-only place in the auditorium, I could see that the actor bore no facial resemblance to the great man. He had a van dyke beard, but he slicked his white hair back in the style of Atatürk. His interactions with both the adult chorus and the children increased the intensity of the homage by the chorus and the audience.

This oratorio was blunt with its symbols and emphatic in its secularism. At the end of a climactic song, the chorus turned and threw their wadded-up veils towards the back of the stage: blind no more after the teachings of Atatürk, yes, but also a dig at conservative women in Turkey who continue to wear headscarves today — a practice that had been banned in schools and public buildings by Atatürk. A giant screen that spanned the back of the stage featured different photos of Atatürk throughout the program: him in a western tuxedo, dancing at a wedding, driving a tractor to encourage mechanized farming, teaching the reformed, Latinized Turkish alphabet to schoolchildren.

As the oratorio closed, the symbols were brought back to the fore by chorus members, and the actor approached the front of the stage to address the audience. Even with my limited Turkish, his message rang clear: “People ask, ‘where is Atatürk?’ ‘who is Ataturk?’ I tell you we are Ataturk.”

And with that wish for a nation of reformers, liberators and modernizers — not just one figure in the history books and remarkably alive in Turkish hearts & minds today — the oratorio came to a close. The audience applauded wildly, and this image smiled down from the screen above the stage:

One by one the performers took their bows: the male and female choristers, the children, the actor, the orchestra. The director came up last and bowed to rousing applause. But he wasn’t done, because he turned and gestured towards the image of Ataturk above the stage.

The performers and the crowd roared with applause for the man whose memory was at the heart of the Commemoration Day festivities, and still in the hearts of his countrymen and women.

And that’s where I learned a key, new insight about Turkey, a country that has taken a “slingshot approach” to modernity. In its final centuries as a sultanate, the country had been pulled backwards — it had nearly been broken by World War I and the subsequent invasion by Greece. Atatürk had been a shot, releasing all that pent-up ability and lunging the country forward with dizzying speed from a backwards sultanate to a modern, Muslim nation.

The history of the nation since then — all too often dragged back, back, back towards a bygone age, then SHOT forward into a new one — was a testimony to other Atatürks in the nation’s history.

And on this Commemoration Day with this oratorio, composer Tolga Taviş left viewers with the hope that — despite deep divides between secularists and conservatives — the country’s next SHOT forward was only months or years away.

It is wonderful to see that the model of Ataturk still has great resonance, at least in the western part of Turkey.