Close Viewing: 20th-century Turkish art at the Arkas Art Center

How Turkey endured a century without empire -- without rebellion -- and found a middle ground in a violent era.

At the beginning of the 20th century, Turkey may not have been the world-dominating power it had once been, but its Sultan was a peer to the emperors of Austria and Germany, the Russian tsar, and with the kings of England and Italy, among other rulers of Europe and Asia.

They ruled over nations who didn’t speak the “king’s language.”

They were willing to sacrifice millions of their subjects’ lives to grab territory from other emperors (or fewer in battles with idigenous armies where they had overwhelming technical superiority)

When the Great War broke out, Turkey joined the Central Powers and set out to reclaim territory from the Russian and British empires. By the end of the war, of course, it lost territories in Arabia, Iraq, Palestine and Syria to the British and came dangerously close to becoming a colony itself before uniting behind Mustafa Kemal Atatürk and charting its own path through the 20th century.

This post isn’t meant to re-tell Turkish history. It is ostensibly a review of an art exhibition at the Arkas Art Center in Izmir (open through 28 December 2025). I begin with a look at the beginning of the 20th Century to show how similar Turkey was to European imperial powers at that time and to pose the question that I asked myself as I toured the exhibit, Tradition and Modernity: Turkish Painting in the Arkas Collection (1920-1970): What does Turkish art show about the alternative path the country took to that of its western peers in the 20th century?

20th-century Turkish Art

I have already had a chance to ask this question thanks to a fantastic exhibit of 20th-century art that is on permanent display at Izmir’s Art Factory. What one sees there — and in the Arkas collection — is Turkish artists playing catch-up with western trends such as Impressionism, Cubism and Social Realism.

There are some very good paintings at the Art Factory, but the sense of catch-up and appropriation of western trends discouraged me. Turkey led the world in art for centuries: the tulips of Iznik ceramic tiles are among the greatest motifs in any culture, Ottoman miniatures were beautiful. Aside from the fact that landscapes show areas around Istanbul caravans or camel caravans, I saw little that equaled the creativity I had seen in western collections.

What the Arkas Exhibition showed me was a key element of 20th-century western art that was missing from Turkish collections, and it made me think anew about Turkish history and the Turkish mindset, which is my mission in this Substack — a thread running through most of the essays I have published here.

Just six months after the Armistice that ended World War I, Greek forces landed in Izmir and began a land grab that threatened to parcel out the Turkish heartlands: Britain occupied Istanbul, the Italians occupied the southwest, and the French claimed the southwestern areas near the Syrian border as well as former Ottoman colonies of Syria and Lebanon thanks to the Sykes-Picot Agreement of 1916.

The war continued another three years until a Turkish victory expelled the Greek Army — and eventually Greek residents — from the Anatolian Peninsula. This was followed soon by the removal of British, French and Italian troops.

Turkey had begun the 20th century as an empire, but it would not become a colony. It is one of only a few Asian nations — Persia and Thailand are the others which come to mind — that were not colonized. This kept Turkey from the same sad fate as Algeria, Egypt or Syria, a sort of middle ground of 20th-century development.

Like its former Central Powers allies, Italy and Germany, Turkey fell into one-party, nationalist rule led by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk. Unlike his Italian and German counterparts, he eschewed imperialism. An early opponent of Turkey’s entry into World War 1, he carefully kept the country out of broader conflicts. Despite the fact that he died in 1938, a year before the outbreak of World War 2, Atatürk’s wishes were followed and Turkey stayed neutral throughout the second World War.

The second World War set off two movements that defined the latter half of 20th Century art: abstract expressionism and Pop Art, Minimalism, and Post-modernism. Yet as I toured the paintings in the Arkas Collection, which included 25 years of the post-WWII era, I found these movements missing.

The Arkas Collection

The exhibition covers the upper two floors of the French Consulate in Alsancak, a picturesque location in its own right, looking out at the Gulf of Izmir from the first row of buildings in the city. The first story consists of landscape paintings, each room with its own theme. The second story holds collections of still-lifes, portraits (men and women are in separate rooms), and village life.

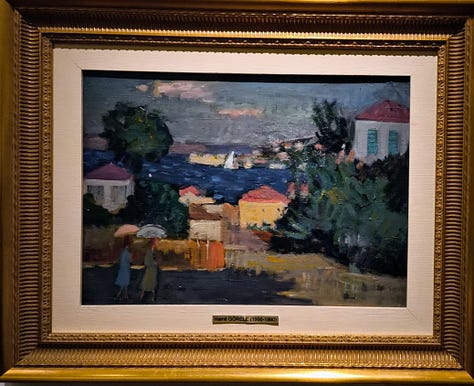

The opening gallery holds a series of landscapes by Hoca Ali Reza (1858-1930) painted in the 1920s, showing elements of Impressionism and celebrating the beauty of coastlines, something that Turkey has in abundance. The style of these paintings is explained in the 2nd-floor entry gallery, which features photos and accounts of a group of Turkish artists who traveled to Paris for study in the 1920s.

When I entered the first room, I was drawn to three images of the Rumeli Fortress, which was built by Mehmet the Conqueror in 1451 on the Bosporus to guard the approach to Istanbul from the Black Sea. These three paintings — two images are by Cevat Erkul, the third, by Ibrahim Çallı is painted from the very same view as one of Erkul’s paintings: framed by two of the three round towers that make up the fortress, looking north along the Bosporus. Erkul’s image flirts with Cubism and makes me think of Cezanne, but it never approaches the abstraction of great Cubist art. It was my favorite of the three (it is the leftmost painting among those in the image below.

This gave me a hint of one of the highpoints of this exhibition: the placement of different artists’ interpretsation of similar subjects side by side, which lets viewers understand the choices artists make and compare their individual styles.

In the second room, there was a pairing of paintings from the Princes Islands in the Sea of Marmara south of Istanbul, including two that seemed to have been shot from opposite sides of a lake. In the corner, two paintings sat side by side showing the gardens of mansions, each shaded by a huge tree.

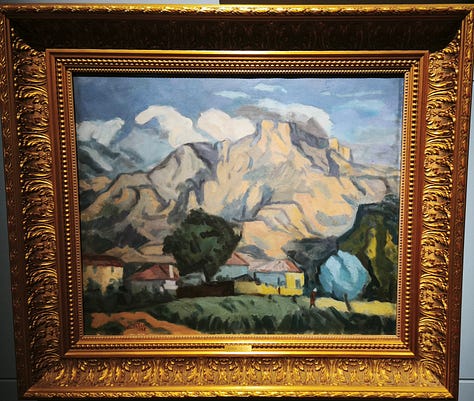

The fourth room featured more landscapes — leaning more toward the abstract. Cemal Tollu’s “Landscape from Manisa” (1935) was one of my favorites of the exhibition: it’s huge, Cubist Mount Spil towers over the city (two of the most notorious sinners of Greek mythology, Tantalus and Niobe, lived on that mountain).

In the landing at the base of the stairs, two seascapes complete the collection of landscapes. Ibrahim Safi’s “Port of Alsancak” (1960) is another one of my favorites, its textured, thick strokes of oil paint capture a windy day on the seaside near the Alsancak Ferry Terminal — which is just a few hundred meters from the site of the exhibition.

At the top of the stairs I found Hulusi Mercan’s “Jazz Orchestra,” a pulsing, dancing exemplar of Cubism that I found entrancing if a little disappointing. I had come to the exhibition to learn about Turkey, and an amazing painting set in Paris just didn’t satisfy me. It’s the kind of painting I would show students to say, “look at this piano, the drum set, the perspectives…THIS is Cubism!” It’s not the kind of painting that makes me think, “THIS is Turkish art!”

Reflections on Turkey and Turkish Art

Last autumn, I reviewed an exhibition of Pop Art that I had visited in Izmir’s Kültür Park. Looking back at my notes, I didn’t see any examples of Turkish artists in the exhibition. As I wrote at the beginning of this review, I found no examples of Abstract Expressionism, Minimalism or Pop Art here, despite the fact that the exhibit extends to the 1970s, an era in which these movements were ascendant in the West.

When I first saw the title of the exhibition, “Tradition and Modernity,” I expected conflict and dramatically contrasting styles. I didn’t find them. Tradition evolved into Modernity at a less intense pace than the Ottoman Empire changed into the Turkish Republic. Perhaps art was a refuge from these dramatic changes, rather than a driver of them — as it became in the West.

Modernism began in the West after World War I. Surrealism and Dadaism captured the meaningless reality of a Europe sapped of millions of its young men and women from war and plague. The even greater destruction and the vacuous morality of World War II led to even more abstract forms of art in the nations that waged that war.

At the same time, Turkey maintained a precarious peace under the leadership of İsmet İnönü, Atatürk’s successor and close confidant who ruled until 1950. The focus of the country was on secularism and strengthening the social reforms since the Turkish Republic’s founding in 1923. (One unwritten theme of the collection is secularism: I found no abstract paintings there, and I cannot recall any images of mosques either.)

In 1950 Turkey’s first democratic transition of power took place with the conservative Democratic Party, which ruled for a decade until a coup returned İnönü to power as prime minister until 1970, the year that this exhibition ends.

Last November I attended an oratorio that celebrated the life of Turkey’s founder, and I had the following epiphany:

[The oratorio, “Sensin Atatürk!”] reminded me of snippets of plays I had seen from the 1930s and 40s, an era of political optimism and Social Realism. Yet this was 2024. I thought of the public art that I had seen here: statues of Atatürk, yes, but also statues of happy families, dancers, shepherds herding sheep. Social realism continues in Turkey to this day, and the commemoration of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk — frozen in time by his death in 1938, when the artform was at its most popular — keeps it alive and thriving.

Again with the Arkas Collection, there is an idea here: that Turkish art and music moved from Ottoman classicism and early-republic Impressionism to Social Realism in the 1930s. This is the place where it stopped its development in the 1930s — and were it remains, now seen as a golden age by children of the 21st Century and fixed by the veneration of Atatürk.

Can I get all this from a collection? After all, the selections in this exhibit were made in the interests of collectors — who no doubt understand Turkish culture better than I, but who also spend to suit their preferences. It would be nice to go back to the Art Factory and view their collection of 20th Century Turkish art to see if my ideas hold up.

Notes

For the interest of space, I left out the paintings in the upstairs galleries: portraits, still lives, and genre paintings of village life. I felt that I had proven my point with the works I featured.

I’d love to hear my readers’ takes on these ideas.

I have spent many pleasant afternoons over the past three years staring at Turkish paintings and trying to figure out what they say about this country. I’ll post a follow-up review of the Art Factory collection next fall. As always, I will be on the lookout for temporary exhibitions that pop up in Izmir and the surrounding areas.

Interesting takes. I was in Izmir from Sep to Dec last year, and saw some Picasso at the Kültür Park. The post-Ottoman post-Atatürk history of Türkiye is fascinating and reveals a lot about history of the region and the word. I don’t know much about the colonial interventions as the Ottoman Empire retracted. Seems like we are still seeing how unhelpful Sykes-Picot was in reshaping the region… thanks for sharing. It would still be interesting to see more of the art if you post more of it. I like the Alsancak pier one, I took that ferry a lot. The modern secular history seems to have benefitted Türkiye a lot.