Last week, as I wrote my newsletter, “Worship Among the Ruins,” I did a deep dive into John.

One of the guidebooks I had consulted mentioned the Acts of John, a 2nd-Century account of John’s life. While it isn’t considered a factual account of John’s ministry in Ephesus, a close read gets the reader closer to the mindset of the time and provides tantalizing details about the area.

After months of living in Türkiye and carefully studying stories of Narcissus and Nemesis, I understand better that myths are always “true” and seldom “factual.” They are “true” to the extent that they contain ideas worth passing from generation to generation. And that is what has mattered most to people over the span of history, with factual, scientific-based observations gaining ground in only the last 100-200 years. This has, of course, given rise to the term “fundamentalist,” which describes a person who insists on scientific certainty for texts that never was intended by the writer or the earliest readers.

The Acts of John are quite dense, but after a couple of reads, I understand enough to share a little of what I understand.

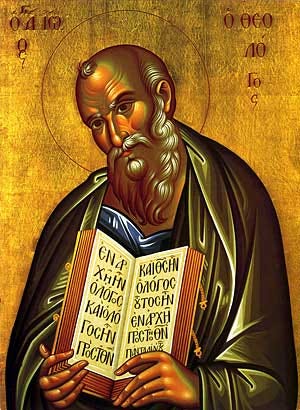

St. John in the New Testament

Christians recognize John, one of the three closest disciples to Jesus during his ministry – a witness to the Transfiguration, the raising of Jairus’s daughter from the dead, among other miracles. He, along with his brother, James, was one of the “sons of thunder” (Mark 3:17).

His name was given to the 4th gospel, which is why one of his sobriquets is “the evangelist.” A writer named John also wrote the book of Revelation, and this book was tied to the disciple when the canon was compiled in the 4th Century CE.

In the Book of Acts, John is shown with Peter, preaching in the Temple after Jesus’ ascension and healing a lame beggar there (chapter 3). They are called before “the rulers, elders and teachers of the law” where they are threatened but otherwise sent home unmolested (Acts 4:5, NIV). No doubt John was among the “other apostles” who in chapter 5 were threatened with death but saved by Gamaliel, who observed that this movement would either disappear of its own accord or “if it is from God, you will not be able to stop [it] (5:39)

Beyond those verses, little more is said of John. I expect that he stayed in Jerusalem, ministering to the Jews. There were three catalysts that could have sent him westward. The first was the martyrdom of his brother, James, which occurred in 44 CE. This fits with the time that John is said to have arrived in Ephesus between 38 and 47 CE, along with his aunt Mary, who had been given into his care by Christ on the cross.

(This would pre-date the arrival of Paul in Ephesus by 7-10 years, yet Paul never mentions John in his letters from Ephesus. To me, this implies a later arrival for John, after Paul, Aquila, and Priscilla’s mission there in the mid-50s.)

The other catalysts, a bit later but logical, would have been the martyrdom of James the Brother of Jesus in 62 CE and the fall of Jerusalem in 70 CE, at which point the church in Jerusalem was scattered.

Now I turn to the Acts of John for the next-closest source on his life.

John’s Arrival in Ephesus

The Acts begin with John hastening to Ephesus. The commentary on the book implies that this occurred on his return from Patmos, a part of an older manuscript that has been lost. Outside the city gate, John is met by Lycomedes, a “praetor” of Ephesus whose wife, Cleopatra, had died [verse 19].

They return to Lycomedes’ house, but the praetor, so upset by his wife’s passing, falls down dead beside her bier [21]. Now there are more Ephesians rushing to the house, once word gets out that Lycomedes, too, has passed away.

Before this greater audience, John prays, “[Lord] give them hope in thee.” And then he says, “Arise in the name of Christ,” and Cleopatra, dead seven days, returns to life [22-23]. This story parallels closely with the raising of Jairus’s daughter: a wealthy person seeking help for a loved one, a multitude, and the presence of John, one of three disciples who followed Jesus into the girl’s funerary chamber.

But an interesting thing happens after Cleopatra returns to life. John takes her to see her husband, now dead, and he invites Cleopatra to resurrect her husband. She follows John’s instructions, says, ”Arise and glorify the name of God, for he giveth back the dead to the dead” [24]. Lycomedes awakes, and the Christian movement appears unstoppable: a multitude of witnesses, a famous couple, both resurrected within an hour. This message is irresistible.

Healing Women in The Acts of John

This is the first of two healings performed by women in the Acts of John, and I think this is significant. The early Christian church gained ground among women and slaves. Considering the 2nd-century audience for whom this was written – no doubt still a collection of these two groups – the participation of Cleopatra and, later, Drusiana, in miraculous acts of resurrection would have been welcome.

A closer look at the experiences of women in the early church is the story of Drusiana, a bizarre chapter, even in a marginally sacred work like the Acts. A devout Christian, she was harassed by a suitor – ‘one… of the brethren’ apparently – named Callimachus [63]. The repeated entreaties cause Drusiana so much stress, that she eventually dies. Still, this is not enough to stop Callimachus, who breaks into the tomb, planning to molest Drusiana’s corpse [70].

At this point, the modern reader shakes his head. Why? Yet this shows some of the challenges that the female faithful faced in Roman society of the day. Early in the account, the writer states that Drusiana had “for a long time separated herself from her husband for godliness’ sake” [63]. Later, in retaliation, Andronicus had locked his wife away in the family crypt, telling her, “Either I must have [you] as the wife whom I had before, or thou shalt die” [Ibid]. No doubt, Christianity affected many marriages. Andronicus eventually converted. Many husbands never did.

Clearly it was a culture where marital boundaries were not respected, even in apparently loving marriages. Also, it is Drusiana who suffers stress from the sexual harassment; there are no consequences for Callimachus. This shows how Christian proscriptions on sexual immorality would have been embraced by Roman women who lived in a world where they faced the treatment that Drusiana endured, even within marriage. In the middle of this story, the writer talks about a group that followed John to Smyrna, which included Drusiana, Andronicus and “the harlot that was chaste.” Talk about an interesting tale and a career-altering conversion!

The whole catastrophe is, of course, turned into a witnessing event. John appears with Drusiana’s widower, Andronicus, at the crypt where she has been placed. Inside, they find a snake-bitten servant lying dead, and the serpent wrapped around the ankles of Callimachus, the would-be necrophile.

Callimachus, after his long night with the serpent, confesses his sins to John, reporting that, during the long night, he had seen “a beautiful young man covering [Drusiana] with his mantle, and from his eyes sparks of light came forth unto her eyes; and he uttered words to me, saying: Callimachus, die that thou mayest live” [76]. John rejoices and pardons Callimachus [78].

John goes on to resurrect Drusiana, and she – in what must be an all-time act of Christian mercy – asks to resurrect the corrupt servant who had opened her crypt for Callimachus [83]. The story of Drusiana is a primary focus of The Acts of John, stretching over 25 of the 115 verses

There are many other miracles in the Acts.

At one point John agrees to take poison when Aristodemus, the chief priest of Artemis promises to convert if John survives. They test the poison on two convicted criminals, who drop dead immediately. John prays, takes the poison, and survives. Then he sweeps his coat over the poisoned men and raises them, too! [XX/111]

John is sleeping at an inn where he is afflicted with bedbugs and cannot sleep. He prays, “I say unto you, O bugs, behave yourselves, one and all, and leave your abode for this night and remain quiet in one place, and keep your distance from the servants of God” [60]. When John’s disciples awaken the next morning, waiting outside the door is a host of bedbugs, waiting to return home. John addresses the bugs, “Since ye have well behaved yourselves in hearkening to my rebuke, come unto your place,” and the pests return to their homes. To his disciples, John says, “This creature hearkened unto the voice of a man, and abode by itself and was quiet and trespassed not; but we which hear the voice and commandments of God disobey and are light-minded: and for how long?” [61].

John also turns pebbles into jewels and gold nuggets to help some disciples win a debate with the philosopher, Craton. The Christians give the jewels and gold away, much to the amazement of the philosopher. He crushes some jewels and asks to have them restored, which John is also able to do. [106]

Insights into the Life of Christ

I reiterate that the Acts of John are not canon, but they offer some interesting insights into Jesus’ life and ministry in verses 87 - 103.

I was fascinated by the physical descriptions of Jesus offered here – much different from the long-haired, bearded figure common in the West since the Renaissance.

“Oft-times [Jesus] would appear to me as a small man and uncomely, and then again as one reaching unto heaven.” This recollection comes amidst a story about the calling of John and his brother, James. Jesus was waiting on the shore as they docked their fishing boat. The brothers see someone on the shore, but they disagree on what kind of a man they see.

James sees a “youth whose beard was newly come” (i.e. a teenager) while John sees an older man who is “rather bald, but the beard thick and flowing [89]. Again, I don’t believe this was written by St. John, but the description is closer to the time of Christ and – to me – far more reliable than that of the Renaissance.

Jesus’ “small stature” is mentioned again in an account of the Transfiguration. John claims to have cried out in fear, at which point Jesus had “caught hold on my beard and pulled it and said to me, ‘John, be not faithless but believing, and not curious” [91].

In a reference to the feeding of the 5,000, John describes a meal where Jesus took his piece of bread, blessed it, and kept breaking it and sharing “of that little [until] everyone was filled, and our own loaves were saved whole” [93].

The question of Jesus’ spirit and his body is addressed several times, and the author of The Acts of John is very clearly gnostic. “Sometimes when I would lay hold on [Jesus], I met with a material and solid body, and at other times, again, when I felt him, the substance was immaterial and as if it existed not at all,” he writes. Later in verse 93, he describes walking with Jesus on the seashore, looking for Jesus’ footprints, and finding untouched sand.

In an account of the Crucifixion, John describes racing back to the Mount of Olives after the trial, only to be called back to Calvary to “hear those things which it behoveth a disciple to learn from his teacher and a man from his God” [97].

A Look at 2nd-century Worship

Finally, as someone who spends a lot of time thinking about Christian worship, I was fascinated by a few glimpses that the author of The Acts of John gives of the worship of the day.

Here’s a look at Christian worship in verse 110

And [John] asked for bread, and gave thanks thus: “What praise or what offering or what thanksgiving shall we, breaking this bread, name save thee only, O Lord Jesu…?”

And he brake the bread and gave unto all of us, praying over each of the brethren that he might be worthy of the grace of the Lord and of the most holy eucharist. And he partook also himself likewise, and said: Unto me also be there a part with you, and: Peace be with you, my beloved.

The Christian service was centered upon bread, thanksgiving, praise, and offering. This is the essence of 2nd-century worship. The prayer, which I skipped over, is quite long and could double as a short sermon.

In verses 94-95 a hymn is transcribed, probably not a hymn dating all the way back to John, but one that reflects worship in the 2nd Century.

It reflects the call and response of worship services today:

Glory be to thee, Father.

And we, going about in a ring, answered him: Amen.

Glory be to thee, Word: Glory be to thee, Grace. Amen.

Glory be to thee, Spirit: Glory be to thee, Holy One:

Glory be to thy glory. Amen.

A house I have not, and I have houses. Amen.

A place I have not, and I have places. Amen.

A temple I have not, and I have temples. Amen.

A lamp am I to thee that beholdest me. Amen.

A mirror am I to thee that perceivest me. Amen.

A door am I to thee that knockest at me. Amen.

A way am I to thee a wayfarer. [amen].

I imagine early Christians sitting around an upper room or a courtyard in the home of a believer, giving thanks, breaking bread, listening to John speak, and singing hymns. This certainly happened, if not exactly the way written down several generations later in The Acts.

The Death of John

Since I dove into The Acts of John while writing a newsletter about St. John’s Basilica and the resting place of John, the death scene in The Acts is relevant.

After the scene where he breaks bread in worship, John tells a follower, Verus, “Take with you some two men, with baskets and shovels, and follow me.” The account continues, “John therefore went out of the house and walked forth of the gates” [111].

Those familiar with Ephesus can imagine his path. He followed the Sacred Way out towards the Temple of Artemis, which would have still been in business despite The Acts’s numerous claims of John’s victory over the temple and its priests. He walked past the temple to the hill to its northeast where he found “the tome [sic] of a certain brother of ours.”

When the grave was dug, John took off his outer garments, climbed into the grave wearing only a shift, raised his arms to heaven, and prayed.

Then he lay down in the grave and died. Dust arose, and this dust was called “manna.” (It was still rising from the tomb 13 centuries later.)

His followers covered his body with a linen cloth. When they returned the next day, the body was gone, only his sandals and breaths of dust rising, always rising, “for [his body] was translated by the power of our Lord Jesus Christ, unto whom be glory” [115].

I read the text carefully for mentions of Smyrna/Izmir. While the city is mentioned several times, John’s journeys here are pre-empted by events in Ephesus, often regarding the pagan temple.

One story I enjoyed was that of the celebration of Artemis’s birthday, every May 6th. The city had dressed itself in white, as tradition held. John walked the streets dressed in black, much to the ire of religious leaders.

This has been a special post for subscribers. Thanks for subscribing. I’ll try to send out deep dives like this one — or myths and legends once a month.

I appreciate your support.