Explain a Meme: Europe's Unhappiest

How a graph became an Immigrant's Tale. A Turkish youth's journey to Europe... and quick repatriation.

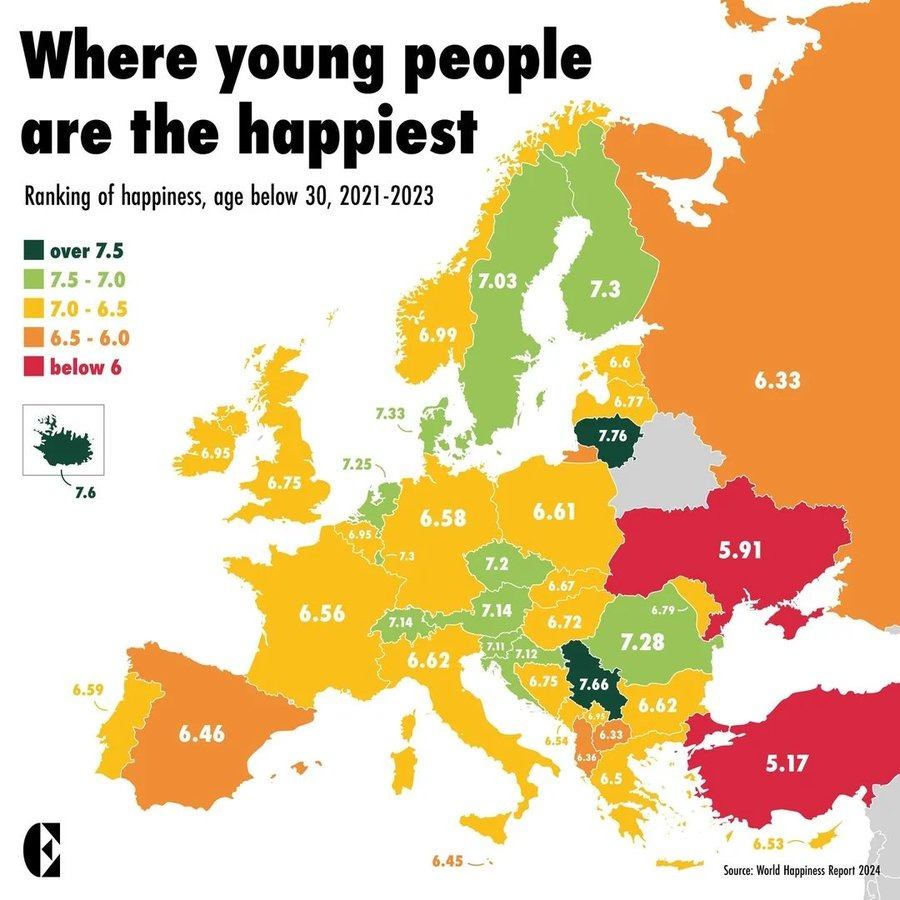

This map caught my eye a month ago: the places in Europe where young people are happiest.

Europe’s happiest young-adults are in Lithuania and Serbia, a surprising development, considering that they are not among the wealthiest nations on the continent. I have never been to either country, so I will leave it to bloggers there to explain this good fortune.

I was also surprised by the least happy nations, at which Turkey ranks at the bottom, below even Ukraine where a bloody war seems set to go into its third year, and where its youth face death along with the destruction of their country.

It is surprising because Turkey is full of young people. It’s median age is among the youngest in Europe. It would seem to be in a position to capitalize on this rising generation to overtake the economies in aging nations to its west.

But that is not the case. Birth rates have fallen for eight straight years now, meaning that this dynamic generation will be followed by a much smaller one. Young people graduating college today are entering an economy burdened by inflation, where the purchase of a car or the rental of an apartment is rising further and further out of reach.

A recent experience I shared (somewhat) with a young friend here might shed some new light on the map that this newsletter is about.

A Member of This Generation: Adam

A few months after moving to Izmir, I met “Adam” at church. He seemed “happy-go-lucky”: a cheerful, funny 20-something who had mastered English watching the YouTube videos of the late Canadian comedian, Norm MacDonald.

In fact, our first conversations were about MacDonald and Saturday Night Life (SNL), the American comedy series on which he was a star in the late 90s. Adam asked about some of the allusions the comedian had made in the routines he had memorized, then laughed once he understood the joke.

At the time I met him, Adam studied international relations at a local university in Izmir. He speaks fluent English, and he even has a northeastern American accent that sounds like he might have been a SNL cast member — more Jon Lovitz than MacDonald, but a fluent accent nonetheless.

I liked Adam so much, that when my sons visited over Christmas break, I asked him to take them out and show them “20-something” Izmir.

As we became closer friends, however, Adam, let me in on his dream to leave Turkey and work abroad. His plans to migrate grew ever more elaborate, it seemed, every few months he had some knew scheme. These included:

Arriving in a country and requesting asylum,

Developing a long-distance romance with a Christian missionary from the United States

Straight-out paying a trafficker to help him enter Canada illegally

Their grandparents bought summer homes during an era of prosperity, but Turkey’s 20-somethings are unhappy, as shown in the chart above — moreso than Ukranian young adults whose nation is under invasion and occupation!

Two months ago, Adam approached me after church and said, “Jay, I’m gonna do it. I’m going to Europe!’

I was happy for him. He planned to visit Norway, then Germany, and finally Portugal. A return to Turkey wasn’t mentioned. It wasn’t expected either.

As departure approached, Adam’s plan came into view. He had obtained a green Turkish passport, which offers special access to European countries without the need of a Schengen visa, which is required for regular, red-passport holders from Turkey. **

Adam had also withdrawn €7,000, which he planned to carry as cash during his travels. I was worried about this, but he said that he couldn’t obtain a credit card. This would have to do.

The week before his trip, he told me that he would travel to the airport from his father’s house in Sefirihisar, a town over an hour’s drive from the Izmir Airport. I offered to let him stay at my place, which is a 20-minute taxi ride. He agreed to come.

When he arrived the night before the flight, Adam was nervous: chain-smoking cigarettes and pacing the floor. I took him out for pizza. Then I showed him the bed in the spare room. “I don’t think I can sleep,” he told me, and he walked down to the nearest tekel shop and brought back a four-pack of enegy drinks for his all-nighter. The cab would pick him up at 5 the next morning.

That night, I tried to prep him for getting into Norway. Adam was a walking “red flag,” I knew: he hadn’t purchased a return ticket, because he planned to fly from Oslo to Berlin after an indefinite time there. He was traveling with a lot of cash. He was single and he had no job back in Turkey. He was a Turkish man with dark eyes and dark hair.

“The guards will want proof that you’re planning to leave,” I told him. “You have to show them that. Show them where you will stay. Tell them what you will see.”

That hadn’t occurred to Adam — sightseeing. When I woke up the next morning, I found several web pages open, identifying sites to see in Oslo.

“Good luck,” I told him, when I went to bed. “Let me know how things go.”

The Norwegian Border

The next evening I got a message from Adam.

“I made it,” he wrote. “But shit I’ve been through, Jay. Oh man. We will talk.”

I didn’t hear from him over the weekend, but four days after leaving, Adam wrote me again.

“Jay, are you busy? My card declined, and they won’t accept cash. I need you to buy me a Turkish Airlines ticket.”

Adam was coming home. I purchased the ticket he needed, and he returned later thaat evening. He didn’t need a place to stay, he told me, he would stay with a relative in Izmir.

His last words were, “I’m starting to get a little sick. My throat is burning, and I feel like I’m gonna have a fever soon. I have a cool story to share, though. See you in church.”

This was six weeks ago. I didn’t get a chance to talk with him at length about his experience until a few days ago.

Time in a Holding Cell

I asked Adam about his entry into Oslo. He described the usual questions that anyone might have faced at the border. Where was he from? Where did he plan to stay? Did he have a return ticket — or one to another destination?

After a few minutes of answering questions, the border guard had called her supervisor, who had come and taken Adam to a holding cell.

“Why are you taking me back here?” he asked.

“You are giving uncommon answers to our questions,” was the reply. Namely this: he had no return ticket — or a connecting ticket — and he had no credit card. (He would later learn that Norway is a cashless society, and he had a hard time buying items — or getting change for what he bought.)

He waited two hours in a holding cell before he could be interviewed by the Norwegian border police. His cellmates were a Swedish man, fleeing an arrest warrant in his home country, and another Turk, who was trying to enter Norway with an Italian passport.

When he finally got his interview, he complained about being held with the other two men. “I’m just a tourist,” he insisted. “Why are you keeping me here?” He showed the cash he had brought, trying again to explain his plans to continue from Oslo.

After six hours, he finally left the airport and went into Oslo to the hostel he had found.

There he found people just like him. Single men from Muslim countries. “You didn’t see any backpackers?” I pressed. “No Australians or Americans?”

He shook his head.

He had gone to church that Sunday, but he hadn’t found anyone there interested in him. “The only people who showed an interest in me were the hoboes and the police,” Adam said. “And the police were a lot nicer.”

Stunned by the frosty welcome at the Oslo airport, and frustrated by the scene in Oslo, Adam had decided to return to Izmir. But the Turkish Airlines office in Oslo wouldn’t accept cash, which is why he had messaged me.

There was one final trial to endure at the airport on his way out. Preparing to leave, a dog had sniffed his bags and alerted the police. Adam wasn’t carrying drugs. He was carrying cash, which had set off the dog.

It was back to an interrogation room. The police assumed that the cash had been earned in Oslo illegally, and they confiscated 20% of it before sending Adam on his way — he has a receipt, and he can file an appeal to return the money, according to a form the Norwegian police gave him that was written in Turkish.

Are you Happy Now?

I asked Adam how he felt about leaving Turkey now.

He shook his head. “I can’t deny it. I like the thrill [of attention by the border police], he said with that goofy, Norm-MacDonald accent of his."

Then he shook his head. “Before the trip, I wanted to leave Turkey,” he said. He rubbed his hand through his long, black hair and adjusted his glasses like a comedian setting up his punchline. “Now… I don’t know.”

Thus ends my tale of one unhappy Turkish youth: back on the soil of his homeland, just as determined as any young person — in Turkey, in Norway, in America, or any other land, for that matter — to create a life for himself and leave his mark on the world.

And for his generation… I hold such hope: hard-working, intelligent, industrious young people — the promise of a continent — hoping to emerge from this present sadness.

“Adam” is the Turkish word for man. The name of this friend has been changed. The quotes and experiences are accurate.

That's a sad, remarkable, yet I take it unremarkable tale. When I lived in Kayseri 2009-11, the many young people I knew were very optimistic about their futures, and Turkey's future, some to the point of grandiosity about a neo-Ottoman empire. I as an American was a kind of refugee from the Great Recession in the US, and the Turks were flattered that a "wealthy" or formerly wealthy American would choose to live in Turkey. I found the people so warm and friendly. I take it Turkey has been sapped by too many refugees as well as internal divisions, a very difficult economy and the devastating earthquake in the South.