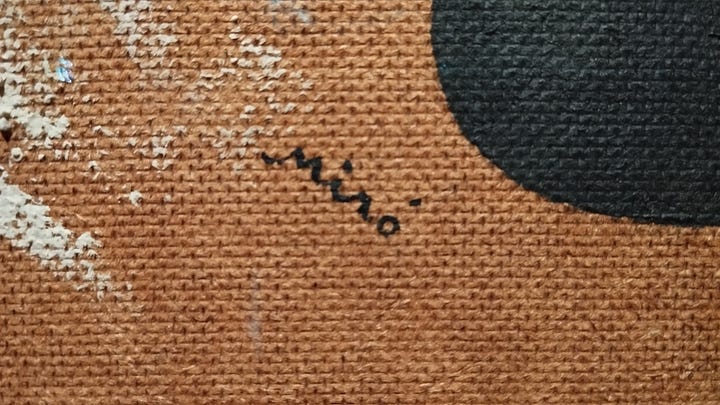

Joan Miró at the Arkas Art Center

The Spanish artist wows with a mixed-media exhibit that spans several movements of 20th-century art.

The rains began in Izmir last week. The weather, which had cooled from summer temperatures only about three or four weeks earlier, is decidedly cooler and windier.

Thus begins the Aegean autumn a wet season that will last until late-January (rains two or three times a week, but in broad fronts, not as scattered showers). The Aegean winter is a bitterly cold stretch of about six to eight weeks after that, ending in early March.

For lovers of Izmir like myself, autumn and winter are really one season: what I like to call “museum season.” So today, I dodged the raindrops to check out a retrospective of Joan Miró at the Arkas Art Center. Located in the upper two stories of the French consulate along the waterfront, the art center has several really thoughtful exhibitions a year, featuring a good mix of Turkish and foreign artists.

Joan Miró, in Context

Would Miró be considered ‘foreign’ this close to the sea? The artist was born in Barcelona in 1893 and spent the final years of his life in a studio on the Spanish island of Mallorca. He was Spanish, of course, but he was a Mediterranean painter, and I’m sure he would have felt at home in Izmir.

Miró’s life spanned three of the 20th Century’s bloodiest conflicts: World War I, the Spanish Civil War, and World War 2. He was 21 when World War I erupted, saved by Spanish neutrality from fighting. Migrating to Paris after the war — where he rubbed shoulders with his fellow Spaniard, Pablo Picasso — he witnessed the artistic movements that grew out of the war: Cubism, Dada, and surrealism, and he added elements of each to his repertoire.

The Spanish Civil War (1936-39) was the great tragedy for the Catalan. Fleeing to Paris, Miró lived there in exile until 1940, when the German invasion sent him fleeing once again, this time to Palma de Mallorca. In 1942 he would return to Barcelona and alternate between the two Spanish cities until his death in 1983.

The Exhibition

The exhibition, Joan Miró: Image, Text, Sign, includes 74 works spanning from 1934 to 1973, spread across seven or eight rooms of the upstairs rooms of the consular building. The entry hall introduces Miró’s life, with captions in Turkish, French and English.

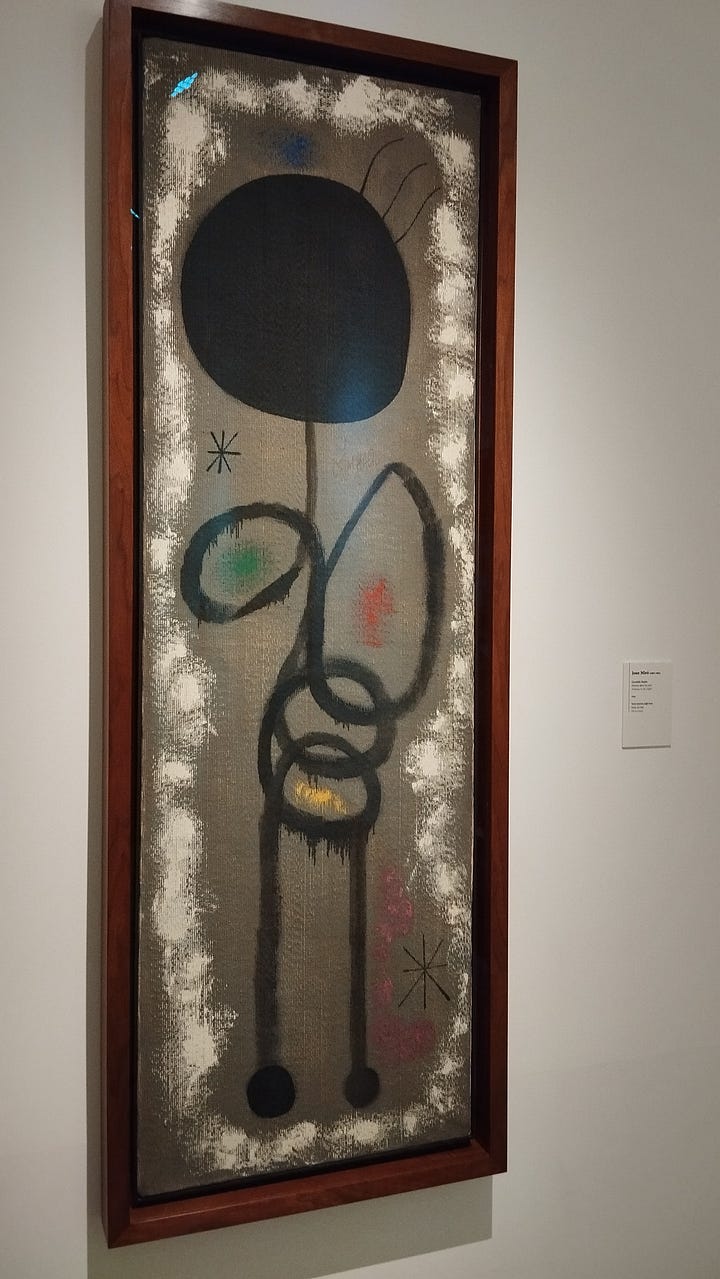

The images in the first room I visited were portraits of men and women. Miró’s women in the years 1934-44 were curlicues, twisted round and round like springs. A great example was “Woman in the Night” (1944), where colorful blotches mark the sexual organs of this woman of twists and turns, even as her face is blotted out. There are stars in this setting, as well as a halo of clouds (stars and birds were the motifs I found most common in this exhibition. But the woman’s face is blotted out, leaving us to guess at the emotions that Miró has implied in her line and posture.

Another woman in this exhibit is “La Fornarina (After Raphael)”, Miró’s take on the highly sensual portrait that Raphael painted of his mistress in 1518-19. In the Renaissance, Raphael’s realism captured the sensuality of its subject, her chest exposed, even as she raises a sheer fabric to cover it.

Miró’s abstract take on the subject flaunts the sensuality of Fornarina’s chest but shrinks her head, which features a Joker-like red smear across the face, black hair and a gold turban, yet also finds a way to add horns to the tree in the background.

A final look at Miró’s women is a cartoonish “Seated Woman” (1939). I had to study this painting pretty carefully until I found the woman: sitting on the branch of a tree, her hair splayed in the wind. It’s a whimsical take, looking ahead to the cartoonish art of the 1960s, 70s and 80s.

In fact, the American artist who came to my mind as I toured the exhibition was Keith Haring, whose cartoonish figures and unique lettering were a hallmark of the 1980s. That’s the thing about Miró. His work spanned the art movements of the 20th Century: cubism, surrealism, dada, abstract expressionism… they are all to be found in "Image, Text, Sign”, and foretastes of late-century street art and graphic designs can be found in his work, too, which was featured at New York’s Museum of Modern Art in several exhibitions in the 1970s, which would have had an impact on artists there.

Mixed Media

The element that amazed me about the art in this exhibition was the sheer number of different media that Miró utilized. Beyond oil and canvas, there are crayon sketches on paper, oil on tarred & sanded paper (material used for roofing in the States), collages on newspaper. He created with India ink, watercolor, goauche, pencil, and even fire. And the paintings were made on materials ranging from woven rugs to masonite, wood, felt and a burlap sack. His works from the Spanish Civil War feature clear, bold colors on the rough, masonite backing, a hint at his state of mind at this time.

Given the trying times in which Miró lived, I expected to see more art that addressed war and politics. I didn’t see it — in this exhibition at least. I traced Modernism through the different stages of his career, but not the horrifying events that drove art to abstraction.

There were plenty of birds and women and stars. A collage of the Columbus Monument was overdrawn with sketches of faces — one of which the explorer’s outstretched arm pointed at. Had it been done in the 21st Century, I would expect it to make a statement about indigenous peoples. But in this context, it was an artist scribbling rounded figures over his hometown’s most famous statue.

Miró’s latest works in the exhibit came from the 1970s. Several abstract paintings on wood and other physical media like felt and carpet reminded me of the grit and graffiti of that era, particularly in New York City. The most recent work, from 1976 was actually a work on masonite, revisiting his work during the Spanish Civil War. In one, he had painted over the earlier painting to create a series of colorful splotches on the rough masonite backing. At the time he made this, he was 83 years old.

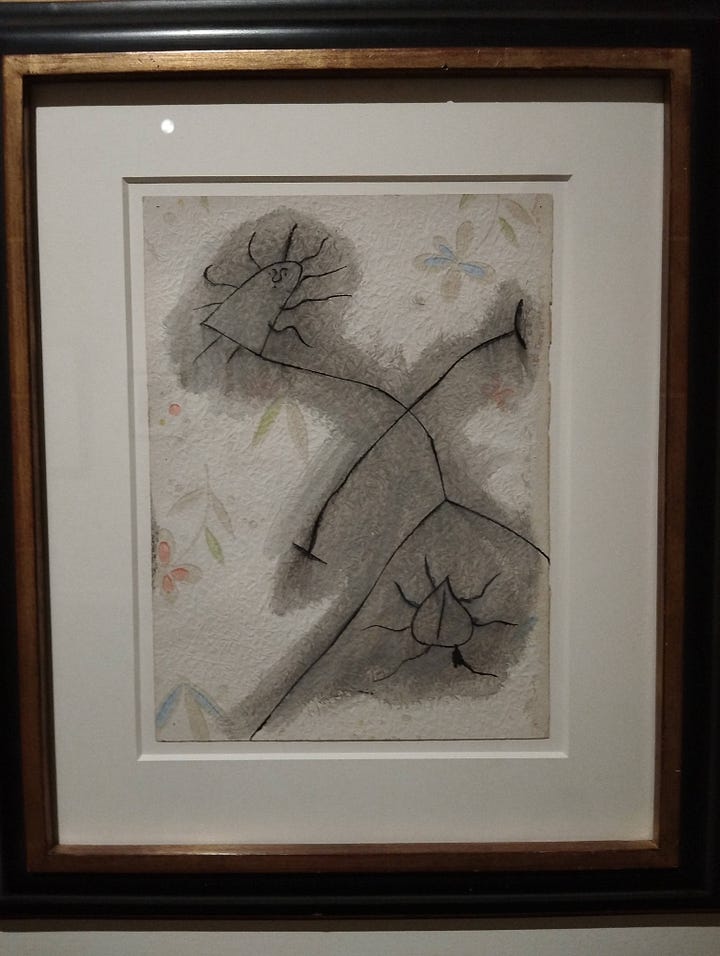

I had two favorite works from the exhibition. The first was “Figures and a Bird” (1936), a whimsical image with a roadrunner-type bird, and amazing, abstract shapes (Miró was fascinated by Japanese calligraphy, and the medium appeared in many of the drawings).

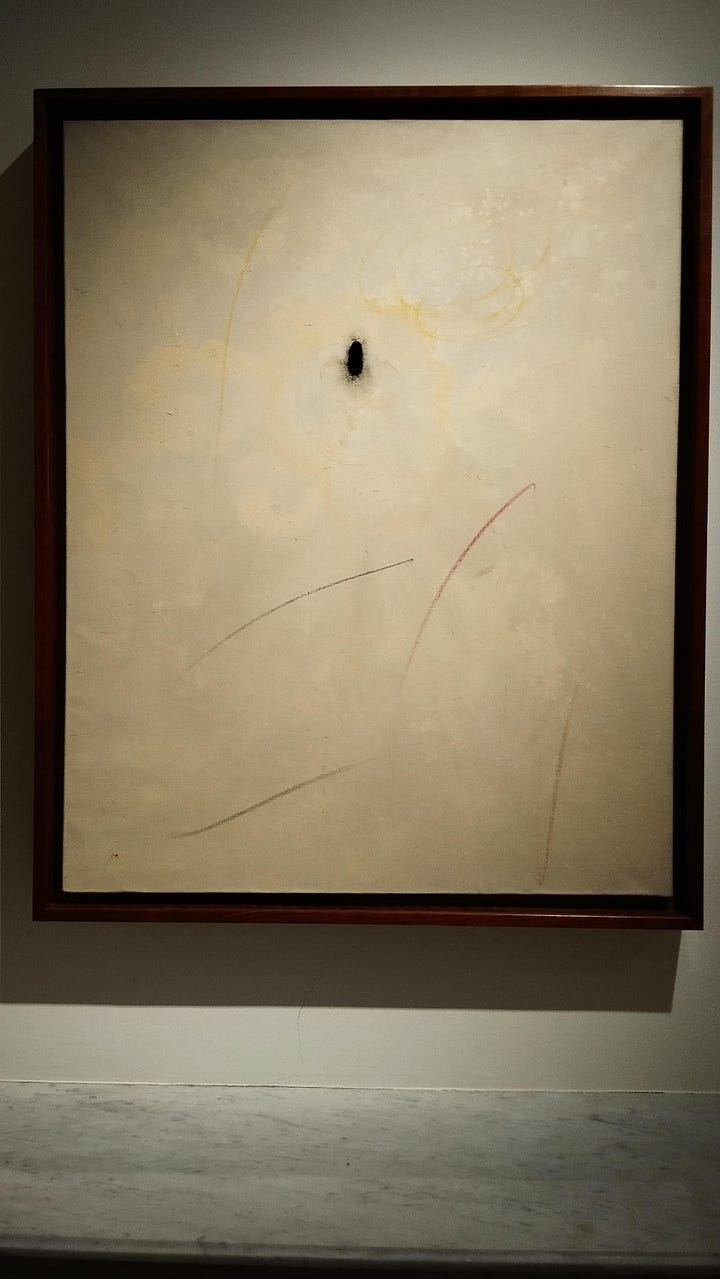

The second was “Painting V/VI” (1960): a pale, yellow sun, barely visible in a white sky, with lines streaking upward below it (either stars or birds, given how common they were in the other ones). In the middle of the sun is a gory, black thumbprint. Is it an eye? Is it a reminder of darkness that could mar even the prettiest scene? It was surprising. It was abstract. And I loved it.

I do have a critique. I don’t like paintings that drip. I don’t see the point, even in abstract work. To me it isn’t creative. It’s laziness. There were a few paintings that I really enjoyed until ugly drips or smears of a paint-smudged finger made me wish for a more thoroughly thought-out and better-executed version.

Joan Miró: Image, Text, Sign runs at the Arkas Art Center through 9 February 2025. Tickets are 150 lira for adults, students and seniors may tour for 75 lira.