Walking with the Greats in Sardis: Cyrus

Sardis is where the paths of the world's greatest conquerors meet. In this 2nd in a series on the three empires that ruled in Sardis, I look at Cyrus the Great of Persia.

About 100km east of Izmir at the base of the northern slop of Bozdağ lies the small village of Sart. Today it lies a few hundred meters off the E96 highway that connects Izmir with Ankara. In ancient times it was a major stop on the Royal Road, a 1700-mile (2600km) route connecting the Persian capital of Susa (modern Shush, Iran) with the Aegean port of Smyrna (Izmir).

The village of Sart was once Sardis, the ancient capital of the kingdom of Lydia — a place where the “greats” of history meet. This part 2 of a series of profiles of these greats, which began with Gyges of Lydia.

The Kingdom of Lydia became a key player in the world economy in the early first millenium, BCE. Gold and electrum (an alloy of gold, silver, and other metals) were found in the Pactolus River that flowed by the city and were also mined in the mountains nearby. The Lydians invented coinage, stamping the Lydian lion on coins which facilitated trade throughout Asia Minor and the Mediterranean.

The Lydians invested huge sums in gifts to various oracles around the Aegean. Along the coast of Asia, two such oracles lay at Didyma and Klaros, where priests of Apollo divined the future for benefactors. But the most prominent oracle was, of course, at Delphi, several days’ walk into the mountains on the Aegean’s western side.

When Gyges (ruled 680-644 BCE) took control of Lydia, murdering the lecherous king, Candaules, and marrying the queen, Nyssia, his rule was precarious. Considered a despot, he faced internal opposition as well as the power of burgeoning Greek colonies along the Aegean Coast. He sent luxurious gifts to Delphi — in part to divine the future of his own rule, and also to gain favor should Greek colonists ask the same oracle for permission to attack Lydia.

In both objectives, we might call him successful. Lydia was an inland empire with no possessions on the Aegean, yet Gyges’ western border was secure, allowing him to expand northward and achieve military success against Cimmerian nomads, whose invasions a generation earlier had defeated King Midas and had conquered the northern Anatolian kingdom of Phrygia.

The oracle also predicted the future of Lydia. According to legend, the Delphic oracle informed Gyges that his kingdom would endure to the 5th generation. This prediction would prove true, and pave the way for the first of the “greats” to set foot on Sardis’ citadel.

Alyattes and Croesus

Lydia reached its apogee under Gyges’ great-grandson, Alyattes (the 4th Generation), who ruled from 600 to 560 BCE. Alyattes conquered Smyrna, the nearest port to Sardis, and he gained influence over Miletus, the region’s commercial center. He fortified the city of Gordion to the north, and he pushed the frontier eastward to the Halys River, which flows from the Taurus Mountain in a great, northwestern curl into the Black Sea.

To the east was the kingdom of Media, sprawling across three great mountain ranges: the Taurus, the Caucasus, and the Zagros. Lydia and Media met in a great battle near the Halys in 585 BC, remarkable for the fact that it was interrupted by an eclipse. Herodotus reported that the combatting sides responded to the omen by calling an immediate halt to fighting and signing a peace treaty. Later, Alyattes married his daughter, Aryenis, to Astyages, the Median prince whose rule began shortly after the Battle of the Eclipse.

Alyettes’ successor was Croesus, the 5th in the line of kings from Gyges. Renowned for his wealth, Croesus funded temples and fortresses throughout western Turkey, including the Temple of Artemis at Ephesus1 and the Apollon at Didyma. He also sent lavish gifts to Delphi, as Gyges had.

Croesus’ wealth couldn’t protect him from developments outside Lydia. In Media, his brother-in-law, Astyages, had been overthrown by Cyrus, son of the Persian king, Cambyses, and the Median king’s own daughter, Mandane. Croesus asked the Delphic oracle if he should invade Media and punish this Persian upstart. The oracle responded with a murky answer: if he attacked the Persians, he would destroy a mighty empire.

Assuming that the “mighty empire” he would destroy would be Persians’, Croesus moved his army into the border region of Cappadochia in 547, crossing the Halys and sacking the city of Pteria.

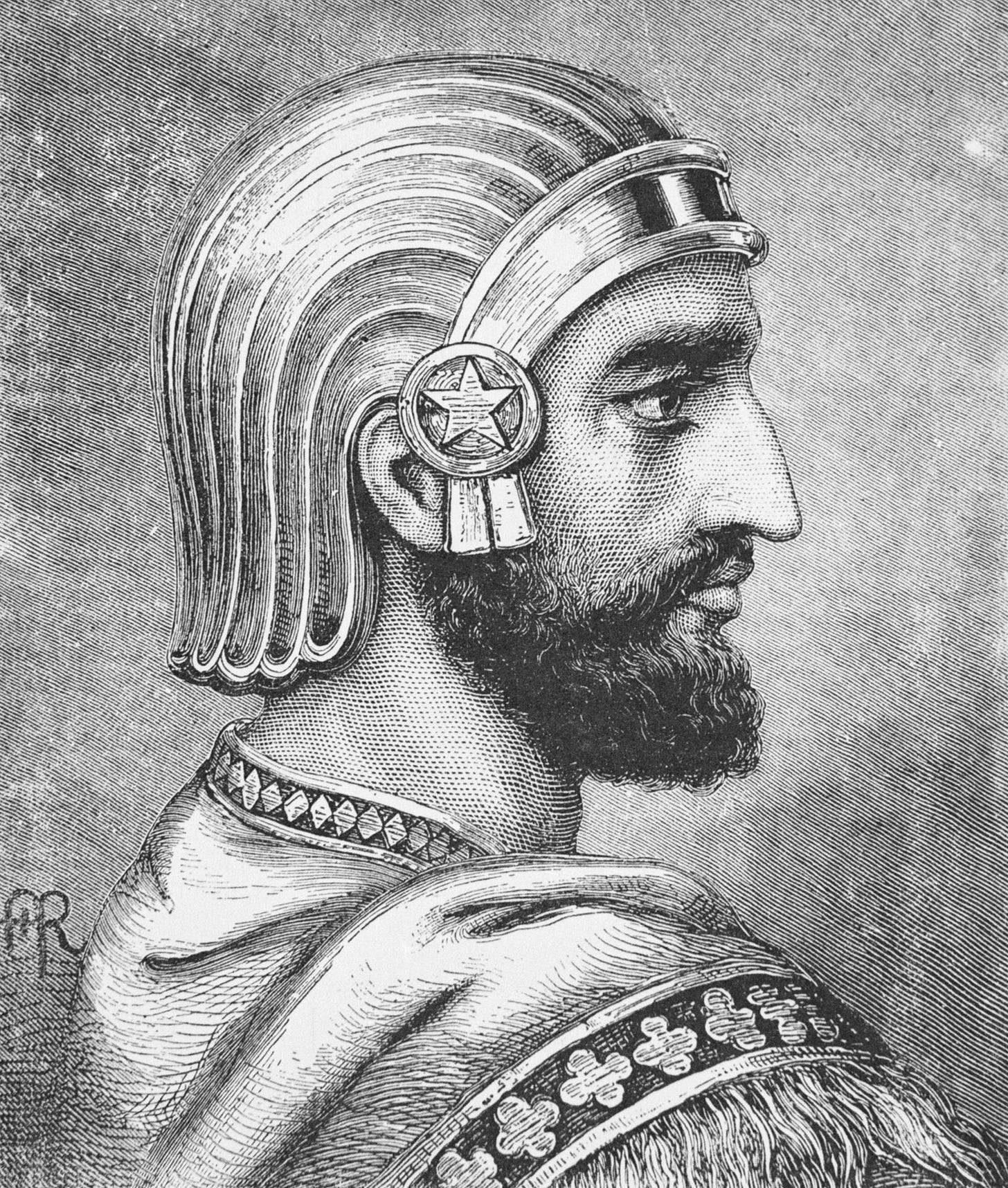

Cyrus the Great

Cyrus, the heir to both the Persian and Median thrones, became king of Persia in 559 and began a war against his grandfather, Astyages, in 553. In 550 BCE he united the Persian and Median kingdoms, strengthening his armies for further conquest.2

War came to Cyrus with Croesus’ attack. He faced Croesus near the Halys in late 547, and the two forces fought to a standstill. With winter coming on, Croesus dismissed many of his mercenaries and retreated toward his capital at Sardis, expecting that the war would lapse until campaign season the following summer. Instead Cyrus followed, his 10,000 “immortals” in the vanguard.

In a second battle, fought just a few miles from Sardis at Thymbra, Cyrus deployed a remarkable strategy for his outnumbered forces. Taking the camels that made up his baggage train, he positioned them to face the Lydian cavalry. The Lydian horses shied at the smell of the camels, opening a breach in the Lydian line through which the Immortals poured. Cyrus’ army won the battle, and pursued the remnants of Croesus’ mighty army to Sardis, where the Persians surrounded the acropolis for a 14-day siege.

The heavily fortified citadel seemed like a safe place for Croesus to hold out for help. The hill is a mesa, surrounded on all sides by steep cliffs. The only way to the top is a narrow, path with deep ravines on either side. Moreover, the legendary founder of Lydia, King Meles, had once carried a lion cub around all sides of the mountain — all but the steepest ravine — summoning magical powers to help defend the hilltop.

One story has it that a Lydian guard, leaning over the battlements at the top of the cliffs, dropped his helmet from the high wall into the steep ravine. Alert Persian scouts watched as the clumsy lookout opened a secret door, descended a hidden path, retrieved the helmet, and returned to the city.

In an attack that evening, the Persians streamed up the narrow trail, forced their way through the secret door, and burst into the city before the beseiged army — looking out over the less-steep parts of the acropolis — could mount a defense.

As Cyrus entered the acropolis that day, he came upon a large fire in the middle of the marching ground. Croesus and his family, on hearing of their impending defeat, had mounted a pyre of wood and immolated themselves there.

Cyrus didn’t have much time to explore the acropolis he had conquered. Wind picked up. Some rain fell. The funerary fire spread to other buildings. Croesus’ palace, temples, barracks and residences went up in flames. The lower levels between the hilltop and the great western roadway suffered less damage.

Even with the city destroyed, Cyrus was impressed with the culture he found in Lydia and western Anatolia. He recruited Sardian architects, as well as Greeks from the city states along the Aegean Coast, to return to Persia with him to his capital of Susa and buid a palace to surpass the splendor of Croesus.

While it would never be the capital of a kingdom again, Sardis remained a capital of the Persian satrapy of Lydia, roughly the size of Gyges’ kingdom but under the dominion of the Persian Empire. The eastern road would be lengthened and renamed the Royal Road, stretching 1,677 miles (2,700km) all the way to Susa.

Eight years later, Cyrus completed his conquests by conquering Babylon (539 BCE). At the time he died in 530, his empire, known today as the Achaemanid, ruled territories that stretched from the Aegean Sea to the Indus River. It would dominate western Asia from 547 to 331.

Traces of Cyrus today

Precious little remains of Croesus’ citadel and the conquest of Cyrus. The acropolis is still impressive, its sides are still quite steep. The hike to the top is one of the most exhilarating walks I’ve taken in Turkey.

Just walking here, though, in Cyrus’ footsteps. That is enough. To imagine the great conqueror and see the world, for a time, from his vantage point.

Other ‘greats’ in this series

Resources I found really helpful for this blog:

Lloyd Llewellyn-Jones’s book Persians: the Age of the Greek Kings, 2022

Google Arts & Culture’s exhibition on Sardis

A tale told at Ephesus relates how Croesus planned to attack the city to add it to the Lydian Kingdom. The citizens stretched a long rope from the city’s northern gate to the gate of the temple complex of Artemis, a place respected as a sanctuary. Amused by the gesture, Croesus held off his attack and used peaceful means to gain tribute from Ephesus. Later, he funded a huge temple complex that lasted for 200 years until 356 BCE, the year that Alexander was born. The rebuilding of the temple created the Wonder of the World that it became in Hellenistic times.

It’s hard for a modern person to imagine the difference between the Medes and the Persians. My simple answer is to describe the Medes of Media as mountaineers, fierce warriors from the ranges that straddle the borders of Iran, Turkey, Georgia and Armenia today. Persians were from the plains to the east of the Zagros. Cyrus’ union of these two great peoples was world-conquering.