Aegean Tale: The Sibyl & the Newborn King

A Christmas tale from Erythrae, an ancient site west of Izmir and home of a famous "sibyl" or prophetess. Part 1 of 3.

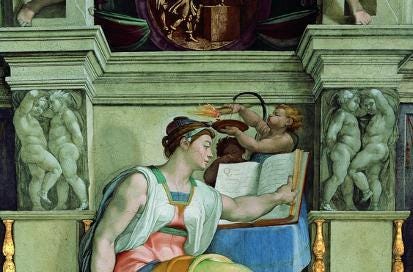

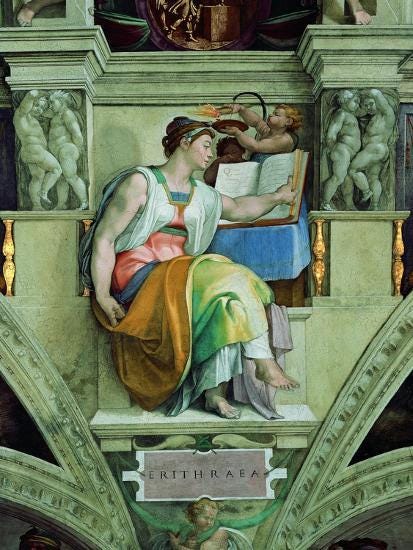

The Sistine Chapel in Rome contains life-sized images of twelve prophets squeezed into its pendentives, the triangular spaces between the arches of the room. Perched there are seven men and seven women who foretold the arrival of Jesus Christ.

The seven men have names familiar to those familiar with the Bible, for they are prophets whose names entitle the books they wrote: Joel, Zechariah, and Jonah, among others.

The five prophetesses, or sibyls, include the most famous fortune-teller of the ancient world, the Pythia of Delphi. The other sibyls are identified by the locations of their oracles: Persia, Cumaea, Libya, and a town whose name sounds like a sigh: Erythrae.

The city of Erythrae lies on the western coast of Turkey. It is sheltered from the Aegean by one great island, Chios, and a line of tiny offshore islets that provide calm, safe harbor. Today it is a small seaside neighborhood of Litri, a part of the town of Ildır, about 74 km west of İzmir.

During the Iron-Age migrations of Greek colonists to western Anatolia (900-700 BCE), a bustling city grew around the slopes of Erythrae’s acropolis. Atop this hill was a temple of Athena with commanding views of the shoreline to the west and north, as well as the foothills of Mount Mimas to the east.

When foreign ships docked in Erythrae, however, their delegations seldom climbed to the acropolis. Instead they followed the shore to a promontory on which stood a round, two-story, stone house. Within the house lived a prophetess called the sibyl.

Whether there was one sibyl or many, no one really knew. She was “the old lady who lives on the seashore” for generation after generation of Erythraeans. They also knew her by her name, “Herophile.” It was a name the sibyl held generation after generation after generation.

The sibyl rose to prominence in the early days of the Trojan War, when Achaean delegations criss-crossed the Aegean seeking good omens for their venture against Troy. A group arrived in Erythrae and marched down to see the old lady on the seashore.

When asked how the war would turn out, Herophile replied with a poem. It was written by her scribe onto a stack of leaves – one line to every leaf:

Very long war to come, still

Ilium’s walls will endure, its

Capital will stand for

Ten long, weary years,

Once you reach that mark

Rejoice and praise the gods,

Your goal will be within reach,

Ilium’s pride will be its downfall,

She will break open her gates for

Your gift, and the warriors inside

On whom victory rests, will

Undertake a night raid, throw open the

Ramparts, and your forces will

Sack the city, reaping many spoils

The poem made little sense, but the Achaeans recognized that it contained a hidden message: an acrostic. They laid out the leaves on a table in the Tower of Herophile. The first letter on each of the leaves spelled out the phrase they had come to hear: “VICTORY IS YOURS.”

The ambassador raced upstairs and bowed before Herophile after interpreting the message. “This is very good,” he told her.

Herophile reached out and grabbed the ambassador’s hand.

“Don’t go,” she said. “There is another message.”

“What is it?”

The sibyl sat down and took a long drink of wine. It was strong wine. She drank a cup before every prophecy. It helped her to gain the attention of the god.

Suddenly she stood and – her head dizzy with the draught of wine – raced a full circle around the room, stopping where a window opened out to a view of Mount Mimas. Here she leaned out the window, reaching wide her arms, embracing the landscape.

The wine, the rise, and the running. These were the tools to jumpstart prophecy in the sibyl. Her mind a whir of images and phrases, she turned away from the window, reached out her arms toward the ambassadors, and said, “Beware of Homeros the storyteller.”

“Homeros?” The ambassadors looked at one another. They didn’t recognize the name.

“Homeros! He will tell tales about the war – not all of them true.”

Herophile laughed and collapsed back onto her auguring chair.

“Show me a bard who doesn’t stretch the truth!” the ambassador said. “Meter and myth walk side by side. So long as he reports that we won, he can lie all he wants.”

The Achaeans left and surely, as the sibyl had predicted, in the tenth year of the siege, they pretended to sail away, leaving a huge gift behind, which the Torjans accepted and dragged into their city. That night the warriors hidden inside the “gift” threw open the gates of the city and sacked it.

And later – much later – almost 300 years after the end of the war – a traveling singer from Smyrna stopped in Erythrae for a two-week stay on his way to Chios. He called himself, “Homeros,” and he sang of Troy: of the hero Achilles, and his triumph over the Trojan hero, Hector.

The sibyl, the old woman, Herophile, sat in the back of the hall where Homer sang his tales, smiling to herself, enumerating all the details this poet had left out of the true account. She had been right all along.

Homeros sang of Troy and Achaea, but he lived in Ionia, a collection of city states along the eastern shore of the Aegean created by Greek colonists who had begun displacing the native Anatolians in the centuries after the fall of Troy. Erythrae was a member of the Ionian League of city states – as was Smyrna, the home of Homeros.

Eventually the cities of Ionia came under threat from the great kingdoms further inland. First Lydia rose to power from its base in Sardis. It conquered first Smyrna then Ephesus and then brought Ionia’s smaller cities to heel, Erythrae among them.

Lydia ruled 80 years until it was defeated in a series of battles in 547 BCE between its king, Croesus, and Cyrus, King of Persia, whose empire would rule for the next 200 years, stretching from the Aegean waters that lapped at Erythrae’s shore to the Indian Ocean – from the Black to the Arabian seas.

Soon after the defeat of Croesus, before the first Persian military detachment had even made it to tiny Erythrae, on the furthest reaches of Asia, a trading party arrived in town. Three men, wearing curious headgear, stepped down from their camel train and told of the long journey from the Persian capital of Susa along the Royal Road. They carried bags of sesame seeds and barley flour, and they spoke of – but did not show – luxury goods from a place called India.

The men asked about Erythrae, and when they heard of Herophile, one man – a trader named Shimon – asked to see her.

He carried a beautiful box with him as he journeyed out of town toward the circular coastal tower. Once inside, he waited for the sibyl, eating olives and bread provided by her servant.

When she descended the stairs, they greeted each other. She accepted a beautifully woven Persian scarf. They sat together and chatted the rest of the day.

They spoke of prophecy. Unlike many of her visitors, Shimon had no inquiry to make. Instead he asked Herophile about her experiences: What had she foreseen? Had she learned if she had been correct? What did it feel like to receive a message?

In return, Shimon answered Herophile’s questions about the great king, Cyrus.

“Have you come to ask about your own future?” Herophile asked once the sun sank low over the Aegean, filling the horizon with smooth layers of orange and pink.

The sibyl looked at the scroll and blinked. She had never learned to read. Her prophecies were always written down by a scribe. “What is it?” she asked.

End of Part 1

Shimon smiled. He told her of the city of Sardis. It had been the capital of Lydia and now, after the Persian invasion, it remained an important city. He had been brought there as a young boy from a land called Judea, a land of which he had no memory but of which his parents and the other Judeans in the community at Sardis spoke with passion and longing.

Herophile gestured towards the scroll. “Is that a painting of the city you have there?”

“The city?” Shimon asked. “You mean Jerusalem?” He paused at this word and looked out the window towards Mount Mimas. He looked down at the scroll and unrolled it. It contained writing. He looked at Herophile and smiled. “It contains a prophecy from a prophet named Obadiah.”

Herophile smiled. The words of another prophet, brought to her home here in Erythrae. “And what does it promise you?” she asked.

Shimon read quietly from the scroll. He looked up. “It is not a promise for me,” he replied. “It is for my people.”

The sibyl gasped.

“Your people,” she pursued. “They are in Sardis?”

“Yes.”

“Your people are in Susa?”

“There, too.”

“And in Judea.”

“A few remain,” Shimon said. “Though most were expelled and forced to live in other lands.”

What does the prophet tell your people?

Shimon read:

Dear ones, The day of the Lord is near.

As you have done it will be done to you;

Your deeds will return upon your own head.

Just as you drank on my holy hill,

United, the nations will

Drink continually,

Greeting one another joyously,

More will come, yea

Ever more will come to drink,

Never will so many

Taste the waters that bring them life.There will be deliverance from Mount Zion ;

Holy restitution

Inheritance will be restored to Jacob….

Herophile called for wine. She raised her glass for a toast. “United, the nations will drink…” she said. She smiled.

Shimon reached up with his glass and met her toast. He took a drink, set down his glass, and continued reading.

“Say to the company of exiles who are in Canaan

They will possess the land as far as Zarephath;

And exiles from Jerusalem who are in Sepharad

Return to possess the towns of the Negev.”

Shimon looked up. “Sepharad,” he said. “That is the place where I live today. That is Sardis.”

“And what is the Negev, this land you will possess?”

Shimon smiled. “A region of Judea south of Mount Zion.”

“You sent for this prophecy?”

“No, it was sent to us. We did not seek it out. It came through our community.”

“It was sent to you by the prophet.”

“Yes, it was sent us by the prophet, Obadiah.”

“And you will go now to Negev, then?”

Shimon sighed. “We cannot go,” he said. “It wasoccupied by the king of Babylon. He is the king who banished my parents into exile.”

Thus began a relationship between the Sardian Jews and Herophile, the Erythrean sibyl. Once a year, a small caravan would arrive, and one or more traders would visit the sibyl, share a scroll of prophecy, and drink a bottle of wine.

One year, Shimon wasn’t with the trading party. A man named Boaz visited Herophile instead. He brought greetings from Shimon and news that Cyrus – after conquering Babylon – had allowed the Judeans to return to their homeland. Shimon was, no doubt that very day, in his homestead in the Negev, just as Obadiah had predicted.

Boaz brought a box with a new scroll. He eagerly shared it with the sibyl. It was a prophecy from a writer named Isaiah. It mentioned Cyrus the Great, who had conquered first Sardis then Babylon, then had set Shimon’s people free.

Cyrus will I elevate and

Help him win his battles.

I will make all his roads straight.

Rebuilding and restoring Jerusalem.

Once my people return to their country.

Herophile smiled at this reading. “This is powerful wisdom indeed,” she said. She leaned back against the wall and enjoyed the last drops of her glass of wine. “Do you have a question for me?”

“I do,” Boaz answered. He found another scroll. “This is from the same box as the Isaiah scroll,” he said. “But I cannot tell if the prophecy is also about Cyrus. It doesn’t say his name.”

“Read it to me,” Herophile said.

Boaz read:

The people who are now living in darkness

will see a great light.

They are now living in a very dark land.

But a light will shine on them….

They will be as glad as warriors are

when they share the things they’ve taken after a battle.A child will be born to us.

A son will be given to us.

He will rule over us.

And he will be called

Wonderful Adviser and Mighty God.

He will also be called Father Who Lives Forever

and Prince Who Brings Peace.

Herophiles’s eyes were closed. “It is not about Cyrus,” she said. She didn’t tell why.

She opened her eyes and looked at Boaz with clear, gray eyes. “The child will come,” she said. She smiled, “The child will come.”

Boaz smiled. He rolled up the scroll and handed the ornate box to the sibyl. “May it come true,” he told her. “Have these words writ, ‘the child will come,’ and seal it in this box. I leave it with you.”

Another Son of God

Seasons passed. Occasionally Persian soldiers would visit the city to collect tribute. They stayed well clear of the sibyl’s tower by the sea. Athenian ships often dropped by with trade goods. Increasing tensions between the empire and the city states across the sea suddenly put Erythrae in the center of world events. This increased the renown of the sibyl, who received delegations from Athens, from Byzantium, and from Mausolus, the Persian satrap, based in Halicarnassus.

Mausolus was an inveterate schemer, who participated in many of the rebellions that marked the final decades of Persian rule in western Anatolia in the middle 4th Century, BCE. Each of his wars and turns of allegiance came with the foreknowledge of Herophile the Sibyl of Erythrae. The height of his glorious tomb matched exactly the height of the peak of the Temple of Athena atop the Erythraean acropolis: about 43 meters.

A few years after Mausolus’s death, Persian soldiers withdrew and Macedonians appeared in the agoras of the village. A delegation arrived from Alexander, king of the Macedonians, asking the sibyl if she knew the true parentage of the new emperor. She submitted a response of four lines on four leaves of parchment.

Zest for conflict & glory

Europe, Asia, and Africa will be

United under megas Alexandros

Sovereign of the known world

When the message reached Alexander in his camp near Memphis in Egypt, he clapped his hands in glee. The acrostic the sibyl had sent – the first letter on each of the four leaves – spelled out the name of the King of Heaven, ruler of the gods. Zeus. Zeus was his father – the very answer he had sought.

Still in Egypt, Alexander was crowned god!

End of Part 2

The roadways and agoras of Erythrae and the other cities of Ionia were now full of Greek traders. The Judaeans from Sardis maintained their yearly visits, brought their embossed boxes, and shared their prophetic scrolls with the sibyl. The Macedonians fought among themselves, however, with Greeks from Egypt – the Ptolemies – ruling first, then Greeks from Syria, known as the Seleucids.

Eventually the king of Pergamum brought stability to the region, and when his line died out without an heir, his great empire passed peacefully on to a faraway state called Rome, which in time became an empire under a single ruler named Octavian, who, like Alexander before him, was given the epithet, “the great,” or Augustus as it is written in Latin.

In the 37th year of Augustus’s rule, a ship draped in dark red cloth sailed in among the barrier islands and bypassed Erythrae. It anchored near the sibyl’s tower. Six soldiers, dressed in shining, Roman armor climbed into the launch. An ambassador in a crisp white toga joined them, and they rowed ashore. There they asked for Herophile.

She welcomed them into the second-storey room. She was in her chair of augury, her back to the wide window. The curtains were open, and the visitors could view Mount Mimas on this sunny, spring day.

“State your request,” she told the ambassador, casting a wary look to the soldiers around him.

“I come from the Emperor,” the emissary announced. “I bear his request.”

Herophile smiled. “Ah, the Emperor. Long has he ruled, this Octavian – “

“Augustus,” the ambassador corrected her.

“I know his name.”

The ambassador reached into his toga and pulled out a scroll. He held it in front of him and unrolled it.

Herophile held up her hand. “I know,” she said.

The ambassador looked confused. “You know?” he asked. “I brought it directly from Caesar’s palace in Rome. I was told to open it in your presence”

Herophile smiled at him. She had a beautiful smile. Pearly white teeth and pale, pink lips.

“I know that your Augustus is nearly 60 years old. He has no heir, no hope of siring a son to inherit his kingdom.”

The ambassador broke the seal, unrolled the scroll, and looked at it. His face turned pale.

“The paper you bear asks a very simple question,” Herophile continued. “‘Who will inherit my kingdom?’”

The ambassador rolled up the scroll and replaced it inside his toga. He smiled. “That is exactly what it requests, madam.” The soldiers behind him looked at one another, amazed.

The ambassador bowed again. “You already knew the question. I’m afraid we do not yet know your answer.”

The sibyl called for wine and drained the whole cup at once. She rose suddenly and staggered a little before her chair. Then she spread her arms, turned, and circled around behind the chair and then around the walls of the round room two, three, four times.

The Romans held their places as the sibyl whirled around the room. They fixed their gaze on the mountain outside the window. Five, six, seven times. Herophile had begun to sing. A Greek attendant sat on a stool next to her chair of augury, writing the words that he heard.

At the end of the eight circuit, the sibyl, Herophile, raced to the window and leaned out, spreading her arms wide toward the mountain, still singing the song, although the words had begun to repeat themselves.

The song slowed then ended. Herophile dropped her arms and leaned down bent over the window sill. The Greek scratched a few more lines on the papyrus, stopped and looked up. The Romans remained silent.

They waited many minutes. “Should we see if she is okay?” a soldier whispered in the ear of the ambassador. He raised his hand – a sign to wait.

Finally, Herophile stood up straight, turned, and smiled at the party of Romans.

“Do you have an answer?” the ambassador asked.

“I do.”

“What is it?”

“It is not the answer your emperor hoped for. But it is the only answer I have.”

The ambassador frowned. He straightened his back and rose to his full height. The soldiers behind him snapped to attention. “Who will inherit the crown of Augustus Caesar? Who will rule his vast empire once he is gone?”

The face of the sibyl grew suddenly serious. “It is a boy…” She paused. “A boy living this very day in Judea.”

“Judea?” The ambassador spat the word. His face wore a sour look.

“Judea,” the sibyl repeated. She smiled. “He is the heir of Augustus. He will one day rule Rome and all the world, just as Augustus has done. His kingdom will have no end.”

The ambassador nodded curtly to the sibyl. Without another word, he turned and left the room, descending the stairs to the ground followed by his retinue.

The Greek attendant called after them, “Wait! Do you want the transcript of the prophecy?”

The door slammed their answer from the ground floor, and the gravel path announced Romans’ fading steps back to the launch.

Herophile returned to her chair of augury. “Read it to me,” she said. “I know what it felt like to know this great event. What did it sound like?”

The attendant read from the papyrus:

Judea’s new king is born,

Emmanuel, his name, for he is

Son and sign of God with

Us, for Judeans and for Greeks

Shall he rule forever and ever.Cry out the news from Mount Zion

Hear the song, all peoples

Rush to see God’s greatness, born

In a humble shelter

Swaddled in rags

There in Bethlehem.

With the Romans gone, the scribe carefully stacked the leaves of texts on top of each other in the order they had been voiced by the sibyl. He took out an ornate, carved box, unclasped it, and opened the top. He placed the sibyl’s prophecy inside, took it outside, and buried it on the hill.

Seventy years passed, and there came to Erythrae a traveling preacher named Yannis, promoting what he called, “The Way.” He brought with him stories of a man called “Jesus,” a prophet who had healed and taught in the land of Judea. The Erythraeans listened in wonder to his stories. Many accepted the god Yannis introduced. They were baptized, and they gathered weekly to break bread and drink wine and remember the Judean teacher, Jesus, even after Yannis had moved on to preach in Smyrna.

One day the Erythraean Christians got a letter from Yannis that warned them of false prophets among them:

“Do not believe every spirit,” it said, “but test the spirits to see whether they are from God, because many false prophets have gone out into the world.

“This is how you can recognize the Spirit of God: Every spirit that acknowledges that Jesus Christ has come in the flesh is from God, but every spirit that does not acknowledge Jesus is not from God.”1

The believers looked at one another quizzically. The sibyl was a prophet, one of them said. She was not a part of their community. Was she, therefore, a “false prophet”?

“Test the spirits,” Yannis had written. No one wanted to test the sibyl, lest she curse them or cast a pagan spell. Finally two women in the group volunteered to go out.

The next day they walked to the promontory with the round tower. Herophile sat outside her house, a bundle of freshly picked poppies in her hand. She stood as the Christian women approached and welcomed them warmly.

“Do you wish me to give you a prophecy?” she asked, once a blanket had been set out in the spring sunshine and the guests had been given olives, cheese, and wine.

The women looked at one another. The elder one spoke, “Oh Herophile, we have come to ask if you are a true prophet. We have been told by a wise man that true prophets can only come from God.”

“Tell me about this wise man, Yannis,” Herophile said, leaning closer to the older woman, whose voice had softened with age.

The women gasped. Neither of them had said the name of Yannis, so afraid they had been of the sibyl’s curses. The younger one spoke up and told of Yannis and his teachings. When she uttered the words, “God’s son,” the sibyl raised a hand to silence her.

The sibyl called to her servant. “Bring me the buried, bronze box,” she told him. The servant hurried away. Herophile turned to the women, “Tell me more about God’s son, this Jesus,” she urged.

This was the first time Jesus’ name had been mentioned in the gathering. The older Christian leaned over and whispered in the younger woman’s ear, “This is strong magic she has.”

“She acknowledges God,” replied the younger, “She knows his name.” And the younger woman told about Jesus’ life: his birth in Bethlehem, foretold by Judean prophets, his teachings, his death, and his resurrection 53 spring Sundays before their meeting on the grassy hillock with the Erythraean sibyl.

The attendant returned with a bundle wrapped in rags. Herophile unwrapped it, and a bronze box appeared. She forced open the clasps, rusted shut over the years. She pulled out a stack of leaves.

She laid them out on the blanket, overlapping, with the first letter of each leaf showing. J-E-S-U-S C-H-R-I-S-T the letters read.

The Christian women looked at one another, amazed. The last six letters spelled out the holy name, spoken only among Christians. The sibyl had known it. She had been the first to use it, even while the Savior was still an infant.

They thanked the sibyl and promised to return the following Easter, if not earlier. They returned and told their friends of the amazing prophecy. Once again word of the Erythrean Sibyl criss-crossed the Aegean. She had told great Augustus himself that a Judaean child would someday rule his kingdom.

And three centuries later, during the reign of a Christian emperor named Theodosius, the people of Erythrae built a church atop the acropolis, right next to the Temple of Athena, which had fallen into disrepair and provided the stones for this new basilica. The tower of the sibyl, on its promontory next to the sea, was also abandoned.

The records of the newly consecrated church of that time include among the names of the priest and deacons the name, “Herophile.” (No mention is made of the gender of the church leaders.)

Six inscriptions from the church bear the name. Three were made between Theodosius and the Turkish conquest of the city in 1333. The last of them dates to 1922, the year before the Christians of Erythrae (by then known as Litri) were expelled from their community and resettled in Greece.

The same name appears in each: Herophile, “lover of heroes,” sibyl and foreteller of the Kingdom of God.

And many centuries later, as Michelangelo adorned the ceiling of a Christian chapel in Rome, he added images of those who had foretold the coming of Jesus: Jewish prophets like Isaiah and others the traders from Sardis had brought to Eyrthrae, as well as the Erythrean Sibyl – known to us as Herophile – and other non-Jewish sibyls from Delphi, Cumaea, Libya, and Persia.

Thanks for reading this Aegean Tale. I wish you and your family a very merry Christmas and the best of years in 2025.

1 John 4:1-3