Homerphilia: Penelope's Upper Room

Could Old Smyrna's double megaron have served as a model for The Odyssey?

I’m nearing the end of this year’s study of The Odyssey with my 9th-graders. In this week’s reading, as Homer described the stringing of Odysseus’ bow, we noted this line:

“[Penelope] withdrew to her own room. She took to heart

the clear good sense in what her son had said.

Climbing up to the lofty chamber with her women,

she fell to weeping for Odysseus, her beloved husband,

till watchful Athena sealed her eyes with welcome sleep.” (The Odyssey, 21.394-399)

At the beginning of the school year, we had visited the site of Old Smyrna, one of the places which claimed to be Homer’s home town. There we had learned one of the unique features of the city that had been one of the most prosperous in the Aegean during Homer’s time: it had two large public buildings, a megaron or meeting room (which I suggested was a model for Odysseus’ dining hall where the suitors were slaughtered), as well as a double-megaron, which the site’s guidebook claims is “one of the first examples of multi-roomed courtyard type houses in the Greek world.”

As I read scenes of Odysseus’ return in books 13-21 of The Odyssey, my students took special note of the times Penelope went upstairs to her room — it is also mentioned as a workplace where she and others work at looms.

The Layout of Penelope’s Quarters

It is clear from many points in the work that Penelope had a room upstairs, above the hall where the suitors feasted and interacted with the servants of the house as well as mysterious strangers.

The first reference in the book is Odysseus’ conference with Telemachus in Eumaeus’ hut, just after the father & son have been reunited. Laying out a plan of attack (before he has even returned to his old home), the Great Tactician tells his son, “I’ll give you a nod, and when you catch that signal / round up all the deadly weapons kept in the hall, / stow them away upstairs in a storeroom’s deep recess” (16.315-317).

The house has a second storey. Odysseus indicates that it was used as a storeroom.

Once Telemachus returns, Homer indicates that the upstairs space is Penelope’s. He enters the palace and goes inside — “propping his spear against a sturdy pillar / and crossing the stone threshold, in he went” — where he meets his mother coming “down from her chamber” to meet him (17.28-29, 37). The upper chamber has stairs (or it could be a ladder) leading directly down into the feasting hall.

As the plot approaches its climax, Penelope uses her position upstairs to intervene when the suitors threaten the mysterious beggar. She “descends” from above almost like a goddess, deus ex machina.

“Now down from her chamber came discreet Penelope,

looking for all the world like Artemis or golden Aphrodite —” (17.37-38, see also 18.180-255)

What was the Room Like?

In ancient times, the inner rooms of homes were dark and stuffy. High walls meant thick walls, made of stacked mud bricks. This was the age before arches allowed for larger windows and higher ceilings.

Much living was done on the roof, where a family would sleep on warm nights, and where there was plenty of room and natural light to work on crafts like weaving and food preparation.

Homer describes the room in several places as a “lofty chamber” — the chamber being a closed room, and “lofty” implying a high ceiling.

“Climbing up to the lofty chamber with her women,

she fell to weeping for Odysseus, her beloved husband,

till watchful Athena sealed her eyes with welcome sleep” (1.417-19)

The Home in the Age of Homer

All this led to a deep rabbit hole for me: searching two-storey houses in the age of Homer. Did Penelope live upstairs from the hall where the suitors cavorted? Did the area consist of a workroom or storeroom? What did the archaeological record show?

I found an article by Turkish scholar, Hale Gönül, an architect who published insights on homes among the ancient Greek houses in western Anatolia. She points out that the architectural influences on the cities on the Aegean Coast of Asia were coming from Asia and Africa — Babylon, Assyria, Persia and Egypt — as well as the Greek homelands of its colonists. Homer grew up in a city where Greek influences were supersized by Asian wealth and culture.

During the Geometric Era (900-700 BCE) during which Homer lived, the simplest Greek houses had rooms called oikos, which could be called “living rooms” with an emphasis on the word, living. In The Odyssey, Eumaeus lives in an oikos where he prepares his meals, sleeps, and spends all of his indoor time.

In wealthier areas like Smyrna, multi-rooms structures emerged around the oikos and the outdoor courtyard. They included

the andron - “men’s quarters” for the symposia and actions of the men of the household

Gönül finds no direct proof, but she speculates that due to the separation of the genders in Greek society, there was a gynaikonitis or women’s quarters as well, along with a thalamos, a separate room for sleeping

an open space also evolved between the room, whether it was a large megaron or a modest oikos that was known as the prostas: a wide entry way with the door at the rear and two pillars supporting a wider front.

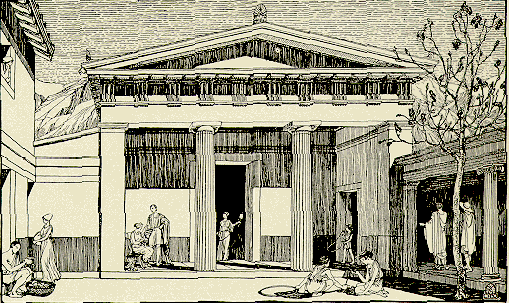

This Hellenistic Era house (circa 250 BCE, about 450 years after Homer) shows the use of the prostas in the entryway to the inner rooms. Despite the high doorway, this house seems to be one storey. (Source: Trans Anatolie Tours)

While there is no proof that there were women’s quarters to balance the androns of the homes in Smyrna, the home was the domain of Greek women, as represented by the goddess Hestia, the veiled keeper of the hearth. Men’s domain was the public square in the polis or city, governed by the god Hermes, protector of cities.

Indeed, while The Odyssey makes many references to Penelope’s quarters and areas where the women live and work, it also begins with a scene where Telemachus enters the realm of men, Ithaka’s agora, where he demands that the suitors leave his palace and asks for help from the citizenry (2.1-163).

Homer grew up in a city where Greek influences were supersized by Asian wealth and culture.

Homer’s model in Old Smyrna

Old Smyrna holds the first two-storey megaron found in the Greek world - a remarkable structure for its day.

The size of four megarons — two side-by-side, topped by a second storey each. The prostas covered only half of the ground storey, and the size of the interior rooms must have been huge — large enough to hold a large group of feasting suitors — or more respectable guests as the case would be in Smyrna.

A look at the floorplan from above provides a unique view of the interior of this palatial home. It has a large prostas that leads into two interior rooms — on the ground floor, at least: an oikos and an andron, given the nature of ancient Greek homes I have described above.

Archeologists have determined from the thickness and the height of the walls that this was a two-storey building, and I will speculate here that the upper storey contained a large storeroom (above the oikos) and a gynaikonotis fitting above the andron.

Homer lived in Smyrna — at least that’s the working theory of this Substack — and I believe he used its environs as models for his works. Smyrna had a busy port, full of sailors bringing tales and detailed descriptions from islands spanning the Mediterranean from Gaza to Gibraltar.

This thriving trade led to a city that contributed many firsts to the Aegean Region: the first walled city, the first stone temple, the first paved street and — yes — the first two-storey stone house.

The two-storey house is a tantalizing1 connection to Penelope and The Odyssey, but I can’t make a direct claim and show that Homer toured it and used the double megaron as the model for Odysseus’ house in his epic.

A terrible earthquake in 700 BCE obliterated Homer’s Smyrna, and Gönül dates the double megaron on the site to within 100 years after Homer’s lifetime, when the prosperous city was rebuilt in an even grander scale than before. The golden age of Old Smyrna stretched from Homer’s day (780 - 700) to 600 BCE when the city was conquered by the Kingdom of Lydia.

The double megaron of Old Smyrna no doubt originated with an earlier structure made of mud brick or timber, one of the wealthiest homes in the city before the earthquake. Homer visited this earlier home. Perhaps he performed there. It stayed in his mind, and he added these two storeys to the many stories of The Odyssey.

A Two-storey Plot Hole?

As I spent weeks thinking about Penelope’s upstairs room and discussed it with the Aegean Region’s most remarkable class of 9th-graders, a sudden plot hole arose.

The penultimate book of The Odyssey ends in a room. It isn’t an oikos because Penelope describes the rooted olive bed as “a secret sign… which no one has ever seen but you and I and a single handmaid, Actoris” (23.254-55).

Since two of the secret-holders are women, this room is no andron. And if Odysseus uses the room, it can be no gynaikonitis. This room is a thalamos, a room for sleeping, reserved for the king and queen of Ithaka.

This raises a question: Is this thalamos upstairs or downstairs?

Based on the pattern of Penelope sleeping and coming “down from her room,” I would place it upstairs in the two-storey house.

I have seen many olive trees in my years in Turkey. They are typically 4 meters tall, and their trunks seldom reach higher than the size of a person before branching out. The rooted bed of Penelope and Odysseus’s thalamos has to be on the ground floor. If it were on an upper floor, it would be “rooted” to one of the upper branches of the olive tree.

This is a tree-top-sized plot hole!

I’m curious what readers think about Old Smyrna’s two-storey house and the Homeric plot hole.

I’m thinking that the final scene was tacked on after the bulk of the epic had been performed — I can imagine mixed-gender audiences clamoring for a happy ending for Penelope.

Homer added a room to the palace for this scene. Who am I to judge?

The real Tantalos was a heroic local king in the area whose grave mound lay outside the walls of Old Smyrna until the 19th Century. Considering how honored he was on this side of the Aegean, it’s hard to believe that the Greeks’ account — stemming from his son, Pelops, who crossed the sea and for whom the Peleponnese is named — is accurate.

I must admit I’ve never read Homer, and I I didn’t really understand the plot hole with upstairs vs. downstairs and the olive tree, but some of my family came from Smyrna and went on to become architects, so they would have found this interesting. I regret not entering Old Smyrna when I was in Izmir, although I was fascinated by the changing-direction traffic lights outside of it. Pretty engrossing stuff!