Travelogue: Didim's Migration Museum preserves memories of Ethnic Exchange

One side of the 1923 Population Exchange between the Turkish Republic and Greece is displayed, but both sides are illuminated.

Didim is a small seaside city on the Aegean Coast between Kuşadası and Bodrum. At the bottom of a hill about 4 km from the beach lies the most awe-inspiring temple in the region, the Apollon.

On top of the hill lies a mosque that still bears a close resemblance to the Greek church that it once was. (Before Christian times, this hilltop was likely the site of a temple to Apollo’s twin sister, Artemis.) It is the last of three Christian churches that once served the community.

Souvenir shops and ice cream parlors line the boulevard between the temple and the mosque, but north of this row of touristy establishments lie six square blocks of stone homes among vacant lots still littered with rubble, remnants of a Greek village called, “Yoran,” that lay here from around the 10th Century BCE to 1923.

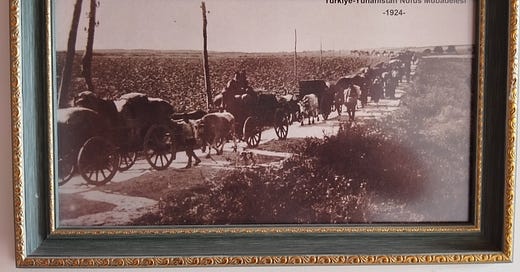

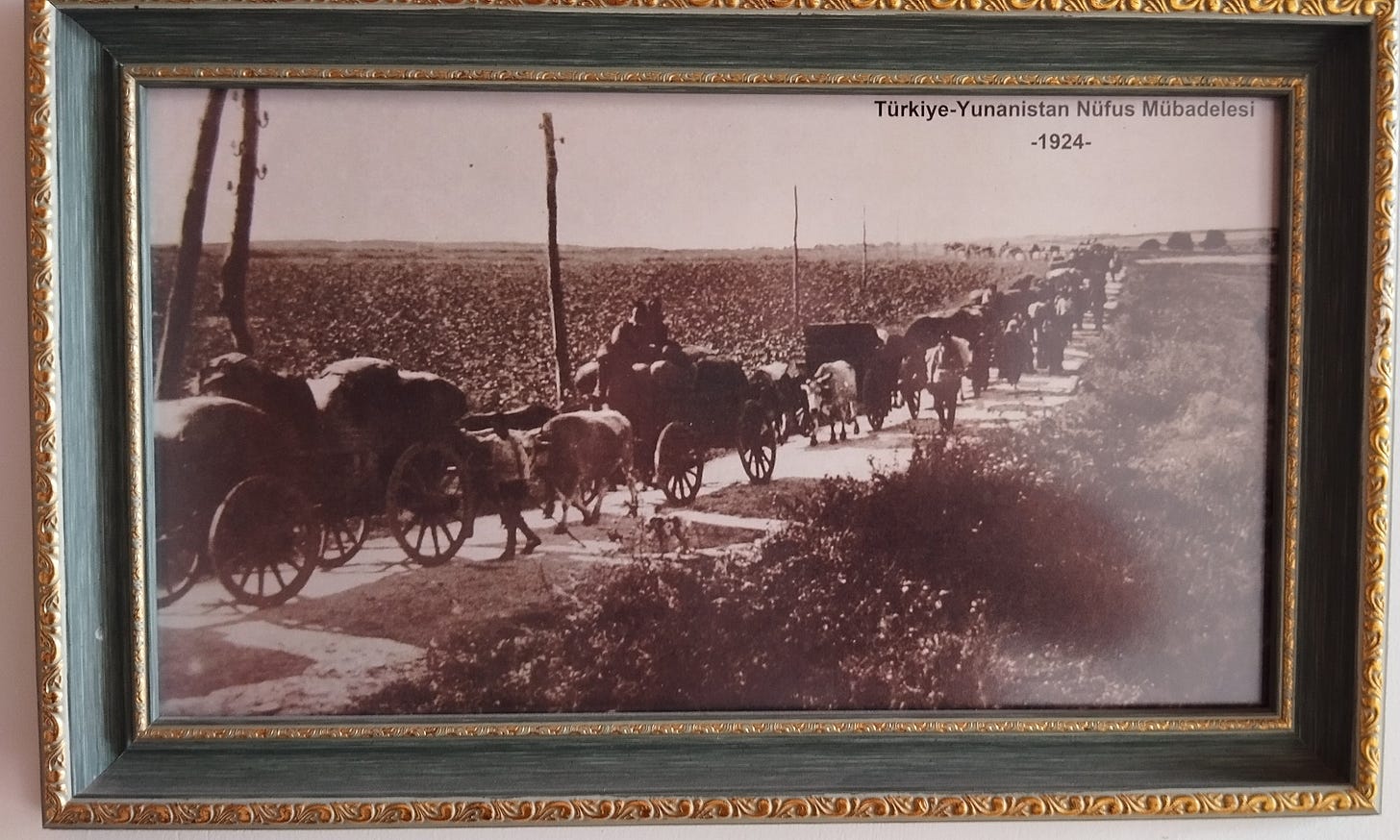

One of the few restored houses is a charming, two-storey house a short walk from the temple. The Mübev is a museum of the Population Exchange of 1923, an expulsion of Christian residents to Greece and a resettlement of Muslim refugees from that nation.

I have seen many ruins of Greek towns along the coast as I have hiked. Many are derelict ghost towns: roofless stone walls with trees growing out of the kitchens. A few have been restored into tourist quarters — especially in seaside towns. Didim’s Yoran is a ruinous mixture of both.

A Tour of the Museum

The museum is divided into seven different rooms, each of them with a different view of home life. Two of the rooms downstairs have been combined into a viewing space. A video there shows period photos of the population exchange, although it wasn’t always clear about which migrants were Greek and which were Turks (everything in the museum is presented in Turkish, but I read most of the panels with a translation app).

Of course, that’s one of the revelations of the museum: those who were forced out weren’t much different from those who arrived from across the sea. Greeks had arrived in the Iron Age (1180-800 BCE), Turks had arrived in 1071, just five years after the Battle of Hastings led to Norman settlement of England.

Just as few would be able to walk the streets of London today and distinguish between a Saxon and a Norman, Greek and Turkish cultures here melded over 8 1/2 centuries. Religion was a distinction. Little else was.

The Mübev House was the home of a Turkish family that resettled from Salonica (modern-day Thessaloniki, Greece) in 1924. The rooms show the traditions they brought with them. The kitchen holds antique utensils, while rooms hold exhibits of clothing, wedding traditions, and home industry like sewing and quilting.

Reflecting on the Population Exchange

The house is a 25-minute tour, at best, but it is a reminder of a challenging time in human history when 1.5 million Christians were expelled from Turkey and exchanged for 500,000 Muslim expelees from Greece. Worldwide it became one of many forced migrations of the 20th Century, vastly overshadowed by the partition of India 24 years later, when ten times that number of people were uprooted.

One of the formative experiences of my life was working at an aid agency, desributing World Food Programme rations to Kosovo refugees during the NATO-Serb War of 1999. Getting to know the refugees there and learning about their expulsion from their homes set in me a categorical repugnance for forced migrations that I brought with me to Turkey.

It’s not hard to see the void left by these expelees. Many of their villages were not repopulated and the land around them lies fallow today. More important, without their economic and electoral impact, Turkey’s development has been affected. Migrants are liberalizing, cosmopolitan influences on a society. As far as I can tell, Turkey is ruled by an Islamist, conservative party. But the next two parties are secular-nationalistic parties, which in western terms would also count as conservative.

But the more I have learned of Turkish history, the more I have come come to see the Population Exchange of 1924 as an act that prevented decades of ethnic violence and stabilized the country through the 2nd World War and Cold War — a time when it found itself in a precarious geopolitical position.

A History Lesson

To understand this, we must look at Turkish history leading up to 1924.

The Ottoman Empire reached its zenith near the end of the 17th Century. As its borders gradually drew back over the next 100 years, Muslim residents of the lands conquered by Austria-Hungary or Russia (the empire’s two great enemies at the time) were forcibly expelled and resettled within the restricted borders of the empire.

The violence increased dramatically in 1821 with the Greek War of Independence. Nationalism and its handmaiden, genocide, raged through Greece. Total victory meant that civilians would not return to “conquered” lands.

Following Greek Independence more defeats followed as the empire gave ground in Croatia, Montenegro, the Caucasus and Crimea, each defeat tied to massacres and forced migrations. By the end of three Balkan Wars in the early 20th Century, western Thrace and Istanbul were the only Ottoman possessions remaining in Europe. Every move of the border coincided with the displacement of tens of thousands of Muslim refugees.

An unstable Ottoman government, under which Christians throughout the empire had lived under general security for centuries, gave way to the Young Turks as World War I neared. These usurpers wielded nationalism to combat their enemies: upsetting the delicate balance that had ruled Anatolia for 850 years, and preparing the nation for a bloodbath.

In the east, Armenian extremists welcomed the Russian Army and assisted its early victories in 1914 and 1915, sabotaging the Ottoman army and massacring Turks in their jubilance. The nationalist government moved the Armenian population away from the contested border areas and sent them on a one-way trip to nowhere, killing between 1 and 1.5 million.

And in the west, the Greek Army invaded Izmir just six months after Armistice and quickly spread throughout western Turkey. Genocide followed in their wake as well both on their advance to the outskirts of Ankara from 1919 to 1922, and their scorched-earth retreat from 30 August to 11 September 1922 which littered the countryside with corpses and burned cities and towns.

These crimes are still remembered here.

Which is why the Population Exchange seems to me now like a noble resolution to an age-old problem. There have been no Armenian uprisings in the northeast or Greek uprisings in the west since 1924. Based on the history prior to that event, there would have been many (the tragic plight of Turkish Kurds in the southeast bears this out).

We need look only at the Balkans, which erupted in genocidal violence again in the 1990s, to understand the horrors that were prevented here.

I was a witness to the victims of these forced expulsions. I remember.

Concluding Thoughts

My lesson at Didim’s Mübev was that a Turkish family, expelled from its home in Salonica, rode in a huge ferry down the coast of the Aegean, and settled in an abandoned Greek home in the village of Yoran. They endured hardship, but they kept the traditions closest to them. They experience marriage, birth, and death in a new land.

I wonder, though, about the family that left the house behind. They must have had money — a sturdy, middle-class house it was, two storeys high! Perhaps a future exhibit there could track down this Greek family and enhance the learning of history here.

But this stone house with its few exhibits is a start. Recognition can lead to reconciliation — and THAT is a trait that ancient cities around the Aegean Sea have long neglected.

If you’d like to read my other newsletters about Didim

Thanks for reading!