Walking with the Greats at Sardis: Alexander

There is only one place in western Turkey where three empires were founded. Sardis. In this 3rd article in a series, I look at a 3rd "great" conqueror: Alexander.

The Bozdağ is a huge mountain that dominates Izmir’s eastern skyline. More than 2,100 meters (7,700 feet) high. It is part of a coastal range that separates the Aegean Coast from the Anatolian interior.

To the east of the mountain peak, a small stream called the Pactolus slithers down into the wide, fertile plain of the Gediz River. Overlooking this stream is a 150-meter-high hill with steep cliffs on all sides.

Ancient peoples found gold in the Pactolus, and as their civilization prospered, they built a fortress on the hill. The Greeks, who came later, would call it an acropolis, or “high city:” a place for an army barracks, a temple to the war god, a vault in which to protect all that gold, and the royal palace. The kingdom that grew there was named Lydia, and the founder of the Lydian Empire was an usurper named Gyges, who founded a dynasty that lasted five generations.

Gyges was the first of the “greats” to rule Sardis, the Lydian capital that grew around the fortress, known in ancient times as “the strongest place in the world.” Over its 2,000 years of occupation, the citadel fell only once, to the 2nd in the line of “greats” that would appear here: Cyrus the Great of Persia, who conquered it in 546 BCE and founded an empire that ruled from the Aegean to the Indus River for the next 220 years.

There was one conqueror still to come. For Westerners, he may be the greatest of “the greats”: Alexander of Macedon (356-323 BCE), who made Sardis one of the first stops in his remarkable 11-year run of conquest.

A Spear in Asian Soil

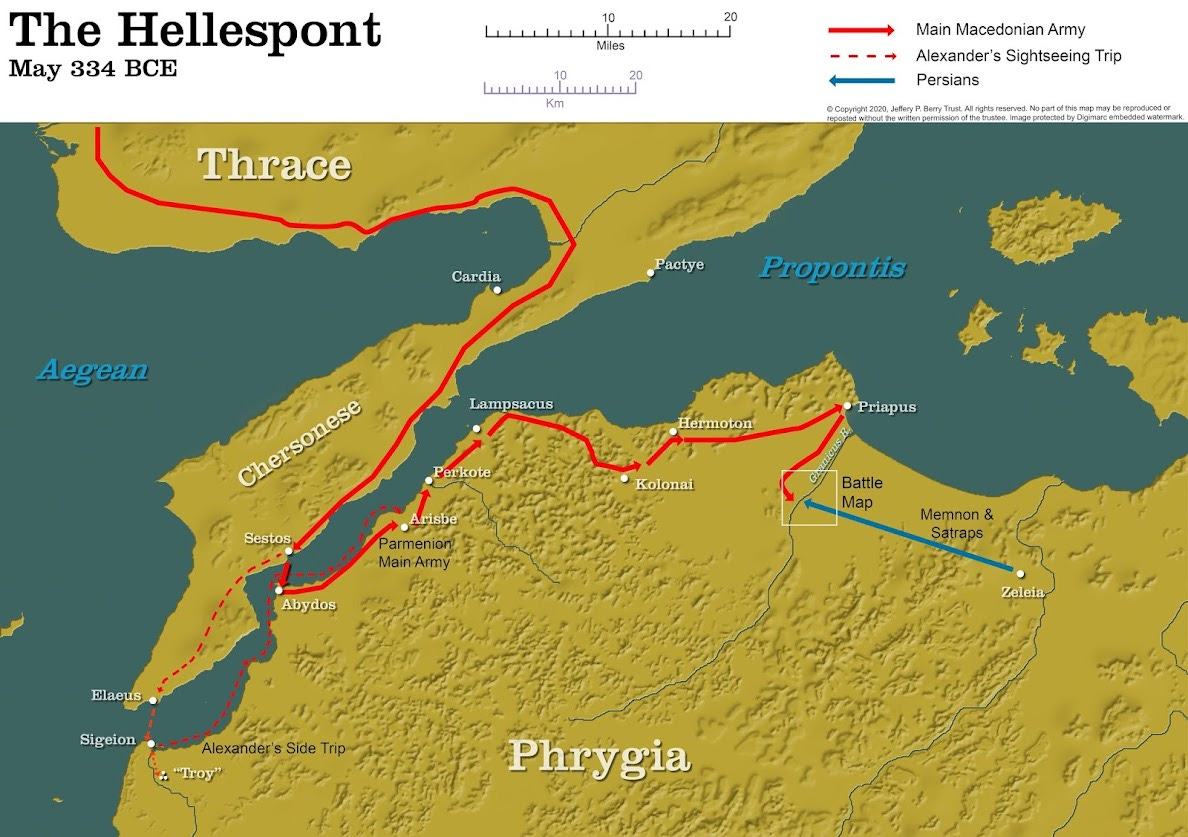

As Persian scouts watched on the eastern shore of the Hellespont in May of 334 BCE, a warship emerged out of the fog. At the bow stood an armored prince, helmetless, his long, blond hair waving in the breeze. A few meters from the shore, he reared back and hurled a spear. It flew across the surf and landed about 30 meters up the beach as the ship’s keel kissed the sandy shore.

To the Persian scouts, this must have seemed more like cosplay than an invasion. They were understandably bemused.

The prince was only 21 years old.

Rather than charging inland, the prince and his bodyguards followed the shoreline down the coast until they came to a peculiar hill that overlooked the beach: the burial mound of Achilles. The prince climbed the mound and paid his respects to the hero of his favorite epic, set among these beaches and fields, The Iliad. All the while, his forces landed further up the Hellespont near the city of Abydos (just 6 km north of modern Çanakkale), disgorging warriors, horses, and supplies.

Continuing his cosplay, the prince crossed the ancient battlefield, entered the city and sacrificed at the Temple of Athena. (A city known as “Troy” occupied the same, commanding place on the Asian shore of the Hellespont from 3600 BCE to 500 CE.) As a souvenir, he took a set of armor from the temple ascribed to be Achilles’, leaving a set of his own as payment. Meanwhile, 125 kilometers north-northeast, a coalition of Persian satraps (governors of Persian provinces), led by Memnon of Rhodes, prepared to block his advance further into Asia.

The Battle of Granicus, May 334 BCE

Memnon proposed a simple strategy to block the prince’s invasion: scorched earth. Alexander’s army of 32,000 infantry and 4500 cavalry could only move 7 to 19 miles in a given day. Deprivation and starvation would be the a sure way to send the Macedonians back to Europe…or weaken them ahead of a Persian counterattack.

But the Satraps balked at laying waste to their own possessions. Fielding a much larger army1, they were confident they could rout the upstart prince. They waited at a formidable bend in the Granicus River.

The approach of the Macedonians would come from the flat bank of the river, while the Persian cavalry would await at the top of a bluff on the other side, raining arrows and spears on the Macedonians as they tried to cross then climb the slope. A phalanx of 2,000 Greek mercenaries waited just behind the cavalry to finish off any bands that made it through the line of cavalry.

Audaciously, Prince Alexander led a cavalry charge up the bank, right at the heart of the Persian cavalry. Success lay in closing the gap quickly between the two armies, as the Macedonians held the advantage in fighting with spears in phalanx formation.

The Persians, espying Alexander at the head of the cavalry charge and eager to engage with the upstart, helped him close the gap. Several companies charged down the bluffs to fight, diminishing their advantage.

Arrian of Nicomedia, in the 1st Century, CE, wrote this account of the battle:

“From the Persians, there was a terrible discharge of darts; but the Macedonians fought with spears. The Macedonians, being far inferior in number, suffered severely at the first onset, because they were obliged to defend themselves in the river, where their footing was unsteady, and where they were below the level of their assailants; whereas the Persians were fighting from the top of the bank, which gave them an advantage…. At last Alexander’s men began to gain the advantage, both through their superior strength and military discipline, and because they fought with spear-shafts made of cornel-wood, whereas the Persians used only darts” (The Anabasis of Alexander, Chapter XIV.)

Alexander, fresh from playing Achilles at Troy, fought bravely — recklessly. A charging Persian named Mithridates charged the prince and “hurled his javelin first at Alexander with so mighty an impulse and so powerful a cast that he pierced Alexander’s shield and right epomis2 and drove it through the breastplate,” writes Diodorus. “The king shook off the weapon as it dangled by his arm… then drove his lance squarely into the satrap’s chest.”

The shield — the shield of Achilles that Alexander had purloined from Troy (?) — held firm. The tip of Alexander’s lance broke against the Persian’s chest armor, but he recovered and smashed the splintered spear tip into Mithridates’ face, killing him.

At that moment a second satrap named Spithridates, brought his sword down hard on Alexander’s helmet, splitting the helmet in two but only causing a superficial wound to the prince’s scalp. Reaching back for a second blow, Spithridate’s arm was severed by a blow from a Macedonian cavalryman named Cleitus the Black, saving the young conqueror’s life.

I mention Spithridates specifically because he was the satrap of Lydia — an empire under the rule of kings Gyges the Great, Alyattes and Croesus; and a Persian province after the conquest of Cyrus the Great. Spithridates’ death would open a clear path for Alexander’s conquest.

With the Macedonian phalanx charging up the bank and closing in, the Persian cavalry broke and fled, leaving the Greek mercenaries behind them without support for the onslaught. The Macedonians carried the day, and the remnants of the Persian army split — some retreating towards Persia, others moving toward Miletus on the Aegean Coast, where naval support gave them a defensive advantage.

On to Sardis, Late May

After Granicus, Alexander could have pushed anywhere. A friend of mine here in Izmir is a tour guide. She told me, “If Alexander had marched (northwards) to Byzantium, he would never have gone further into Asia.”3 He could have pushed inland towards Gordion, the former capital of Phrygia, where he would later untie a famous knot.

Instead Alexander marched south toward Sardis with its impregnable citadel and its commanding position on the Royal Road that Darius the Great had built to connect Sardis with his own capital at Susa, 1,700 miles to the east.

About 7 miles north of the city, a delegation of Sardian elites met him, along with Mithrines, the commander of the garrison there. They surrendered Sardis to Alexander without a siege or a battle. There was no Persian army nearby to defend it.

Thus Alexander became the third “great” to climb to the acropolis and look out over the Geldiz Valley at the fertile lands that now belonged to his empire. One of his first acts was to restore the city to the law of Lydia, the first of many acts that would eradicate Persian culture and elevate Hellenistic culture in Anatolia for the next 1700 years. In Sardis, the site of Cyrus’s most remarkable victory, Alexander the Great proved that both Cyrus’s imperial and his cultural legacies were under siege.

When Cyrus had conquered the acropolis, a fire had broken out, started by the pyre on which the last Lydian king, Croesus, immolated himself. The fire had been whipped up by a sudden storm, and later legends based on the tale claimed that rain sent by the god, Apollo, had extinguished the flames and had saved Croesus and his family.

Once on the top of the acropolis, Alexander direct a group of Argive allies4 to garrison the fortress. He also surveyed they hilltop for a site to build a temple to the god, Zeus. As he and his generals walked across the acropolis, a breeze carried a dark cloud down from the Bozdağ, and a sudden shower soaked a corner that overlooked the Royal Road and the walled city below the hill.

Taking it as an omen, Alexander vowed to erect the temple on that very spot, and his Lydian hosts assured him that it was the very same place where Croesus’ palace had once stood.

After Sardis: June 334

With Alexander’s capture of Sardis, all of western Anatolia lay open. He could have followed the Royal Road all the way to Susa — and a fateful meeting with Darius III— at that point. But there was more conquest for Alexander. The Aegean and Mediterranean ports were still in Persian hands, defended and supplied by the formidable Persian navy.

And Memnon of Rhodes, defeated at Granicus, lingered in the city of Miletus, planning counterattacks against the Macedonian invaders.

But those are wonderful stories for other articles. Alexander’s untimely death — in faraway Babylon after his conquests had ended at the Indus River — led to a challenging era for Sardis, where it was bandied back and forth by descenants of the generals who had divided up the empire.

One of conquerors was another “great,” Antiochus III, who captured Sardis in 213 BCE from his general, Achaeus, who had tried to usurp the city. But that story — and the rise of Roman power in the area — is for another newsletter.

Be sure to explore the other Posts in this Series

Signs of Alexander in Sardis Today

The most remarkable reminder of Hellenistic culture in Sardis is the Temple of Artemis, about 1.5 km north of the village of Sart.

The complex is huge and in a much better state of preservation than the more-famous, world-wondrous Temple of Artemis in Ephesus. The only temple I have found in the Izmir area that is more beautiful is Didim’s amazing Temple of Apollo. The ionic capitals are striking reminders of Greek civilization: wider than a man, and designed to make the enormous roof of the temple look as light as a piece of paper atop rolled scrolls.

The Roman historian, Diodorus, estimated that the Persians had a force of 100,000 men. He is also the source for the 32,000 soldiers I listed above.

Epaulet

Istanbul maintains its captivating effect to this very day. Many would agree that dominion of this one city — particularly its palace complex overlooking both the Golden Horn and the Bosphorus — surpasses the dominion of most empires.

From the Greek peninsula known as the Peleponnese