Homerphilia: Coming home in Old Smyrna

When you visit the ruins of Homer's hometown, unique details from The Odyssey come to light.

My interest in Izmir has always centered upon the ancient writer, Homer, a writer whom I have taught yearly in my English classes since 1995. My first trip to Izmir in 1999 included a road trip to see the ruins of ancient Troy at Çanakkale.

Since I moved here in 2022, I have sought signs of Homer everywhere from the Homer Caves in the hills above Bornova to other site in the area, like Notion, Chios, and Rhodes which also claimed him as their native son.

The ancient site that makes me feel closest to Homer, however, is Old Smyrna/ Bayrakli Mound, the city where he lived and wrote. I have now visited three times — including a field trip with my high school students. I have written a legend about its founding, as well as a tale of the city’s walls which, at the time of Homer, where pearly white landmarks, the finest of any fortifications around the Aegean Sea.

Now that I have lived where Homer lived, and I have seen what Homer saw, I understand so many more details of the epics when I read them with students or for my own edification.

My Grade 9 students are reading about Odysseus’ return home: a goal set up in the opening pages of The Odyssey, and a return amended by Odysseus’ disguise as a beggar. His house is not his own. Instead, it is full of rough, violent suitors who eat up the stores while they wait for faithful Penelope to give up hope of her husband’s return.

The return of the king occurs two-thirds of the way through The Odyssey. As he returns to his home, he describes the scene to his guide, Eumaeus:

“Friend, what a noble house! Odysseus’ house, it must be!

No mistaking it — you could tell it among a townful, look.

One building linked to the next, and the courtyard wall

is finished off with a fine coping, the double doors

are battle-proof — no man could break them down!

I can tell a crowd is feasting there in force —

smell the savor of roasts… the ringing lyre, listen,

the lyre that god has made the friend of feasts.”

— Homer, The Odyssey, 17.290-297 (Fagles translation)

What Home had in mind

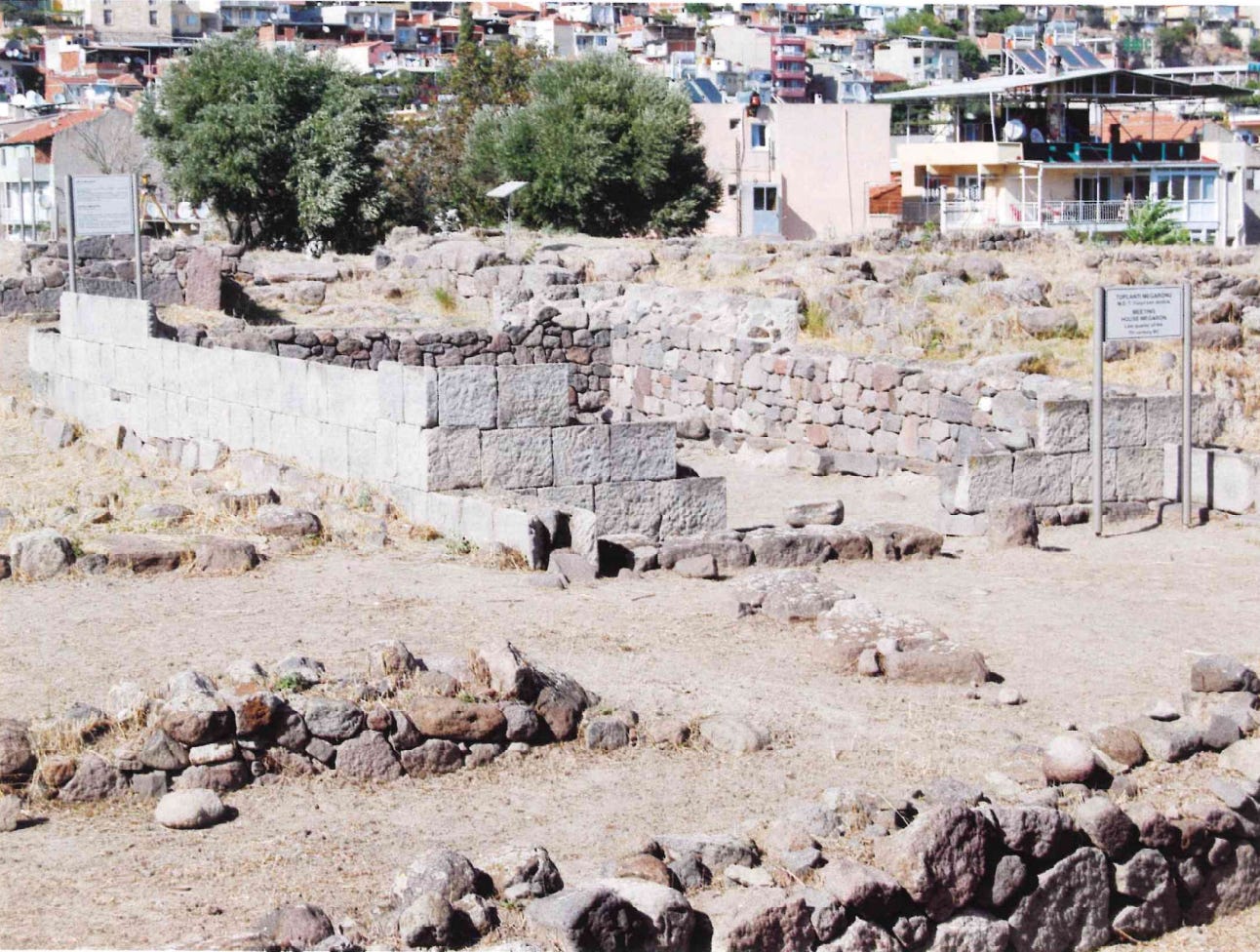

There are two “noble” houses in Old Smyrna: a single and a double megaron. For the purpose of this newsletter, I will assume that Homer’s model for this scene was the single megaron in Smyrna, a huge structure in its day of 73 square meters.

A megaron was an ancient meeting room with a fire pit in the middle and double doors on one end that led to a small portico. I have seen such megarons in many ancient, cities around Turkey, the most remarkable of which was in Gordion, the home city of fabled King Midas.

Looking at the size of the room, helps to put the scenes with the suitors into clear, historic detail. I was riding on Izmir’s Metro subway line recently, and I realized that the size of the megaron was similar to the size of a train car (a little wider, a little shorter, but the same general area of 73m2).

Fifty or sixty suitors wouldn’t have had much room to stretch out sitting within the chamber. They would have been side by side, face to face across narrow tables. The bard — whom the returning king hears from outside — would have sat by the fire in the middle of the room. Pride of place, a table for Telemachus and the family, would have been jammed into one side — hardly a royal dais as I had imagined previously.

(A basic principle of understanding historic people is knowing that rooms were often small and crowded. A typical cafeteria today would dwarf the area of many “banquet halls” of history and myth.)

Secondly, there wasn’t much room for windows or natural light (perhaps a hole in the ceiling to let smoke out and light in. There were no arches, and the walls were made of heavy stone, meaning that any windows would have been small, barely big enough for a person to fit through (Melanthius manages to get in and out with difficulty in Book 22).

“One building linked to the next…”

Homer set Odysseus’ Palace in a rural, far-flung locale, not in a major city of the age like his home city of Smyrna. Surrounding the megaron is a courtyard which is then surrounded by outbuildings… “one building linked to the next.”

One still sees this design in farmsteads throughout the world, particularly in colder climates. Many of the outbuildings are for animals, who are let into the courtyard then out into the surrounding fields through a gate to feed and work. Some outbuildings are storerooms.

Still, in Smyrna we find connected buildings, albeit in a more conventional, urban style.

The main entrance to the site is from the western side, a bluff that once overlooked the Gulf of Izmir but which now rises about 2 km from the present shoreline. At the current site, archaeologists have defined the walls of close-packed houses, with narrow entrances that led to a central courtyard from which five to seven rooms branched.

Expand these Smyrnean courtyards, plop a megaron in the middle, and you have the “noble house” of Odysseus. Yes, the idea of these structures as a direct model is a stretch — Homer traveled widely as an entertainer and no doubt visited countless rural estates to use as models — as well as urban citadels. But Smyrna’s linked buildings were also a reminder .

“And the courtyard wall is finished off with a fine coping…”

The returning king notices every detail, including the coping of the courtyard wall. The coping was the topping or roofing of structures in a complex.

Coping was important in ancient times when so many structures were made of bricks of baked mud. These bricks were vulnerable to rain, so coping was necessary to prevent erosion, as well as to add pleasing aesthetic touches to the complexes.

A variety of coping are reported from the ancient world. Terra-cotta tiles eventually became the standard means of coping walls and roofs, but they were not evident in Smyrna until the 6th Century BCE, according to archaeologist R. V. Nicholls. Stone coping appeared elsewhere but — again — at a date later than Homer.

Nicholls believed that Smyrna’s city walls and buildings were coped with thatch, proposing mud-plastered reeds as the coping for the city’s walls.

Could Odysseus have been referring to the well-maintained, thatched coping of the compound’s walls and roofs in his monologue? Given the conditions in Smyrna at the time, it is likely.

In Book 17, a disguised Odysseus finally returned home. His expression of admiration for the condition of the estate reveals a climax of one of the story arcs of The Odyssey, his 20-year quest to return home.

The details of his revelation reveal the experiences of his creator, Homer, and the city where he composed this timeless epic.

There are many more revelations available to readers of Homer hiding among the ruins of Old Smyrna. If you haven’t subscribed yet, please do so. I’m just beginning to figure this out!

More writings about Homer

Homerphilia: Late Autumn in Izmir