Old Smyrna, City of Aegean Superlatives

Overlooking the suburb of Bayralki, just 300m from the Bay of Izmir, lies Old Smyrna, an archaeological site tracing back 3,000 years

For two years now, I have lived in Izmir, a city that has been known by that name for the past 100 years. In May 1919, it was known by a different name, “Smyrna.”

At that time Greece had landed marines in Smyrna in an effort to take it from the ruling power at that time, the Ottoman Empire, setting off the Greco-Turkish War just six months after the end of World War I. Four years later, triumphant Turkish soldiers, led by Kemal Atatürk, re-took the city, and after a population exchange had expelled Greek & Armenian residents, the city adopted a Turkish name.

That name is Izmir.

The Smyrna before Izmir had existed for over 2,000 years. It was a majority Greek city with many churches and thriving “sectors” where Jews, Armenians and western-European “Levantines” lived and plied their trades. In Roman and Ottoman times, it was a busy seaport, serving camel caravans from Syria and Anatolia as well as trading ships from across the Mediterranean. It was a cosmopolitan, multi-cultural city.

The oldest sector of this “Smyrna” is the Roman agora that lies just east of the bazaar district known here as Kemeralti. It’s an amazing archaeological park — one of my favorite places to spend a Sunday afternoon — with great arches, the only remains of a two-story basilica that stood here, and a long colonnade marking the boundary between the basilica and the grassy lawn where the markets were held.

Visitors to the Roman site have a great surprise in store. This ancient city of Roman colonnades, Ottoman tombstones, and arched foundations is known as “New Smyrna.”

This leads the bemused traveler to ask the obvious question:

“How can any place this old be called, “New”?

The Founding of Smyrna

First, I must explain how old “Old Smyrna” really is.

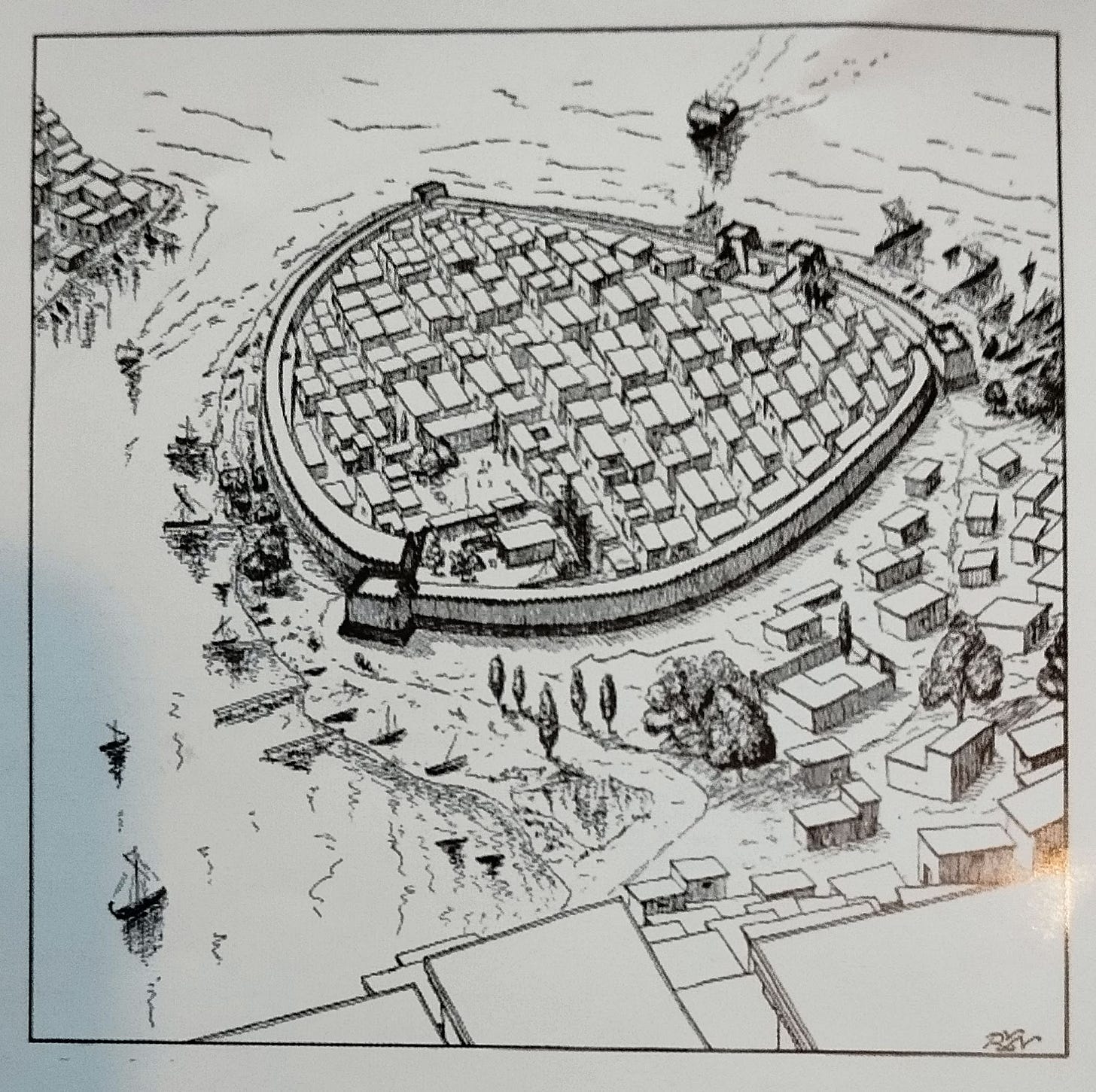

In ancient times, the site lay on a peninsula that jutted out into the very end of the Bay of Izmir. The Meles River flowed past the town and on into the bay, providing fresh water and an estuary where ships could dock. The oldest pottery pieces date back to 3,000 BCE, left behind by indegenous Asian tribes of the time. The oldest buildings on the site date back to the 17th & 15th centuries: homes, workshops, hearths, and paved courtyards.

Around 1100 BCE, colonists from Greece arrived and took over the hill. They called themselves “Aeolians,” a name shared among colonies that settled the eastern Aegean shore from Smyrna north to the Dardanelles, the strait along which Troy lay.

This was a time of dramatic changes in the eastern Mediterrean, where economic collapse and natural disasters had fueled mass migration (an age similar to our own in that regard). At the center of this age was the Trojan War1, a conflict where warriors from southern Greece, then known as Mycenae, landed ships sacked a city and often failed to find their way back home (in reality, Greece itself was concurrently invaded by migrations from Italy and the Balkans — many of these sea raiders never made it home, which makes Odysseus, whose Odyssey chronicles the fate of one of these Sea Peoples2, so singular).

Smyrna became a city in 850 with the completion of a wall around the periphery of the settlement: mud-brick with a stone facing. This is the earliest fortification wall found in the Greek world.3

The answer to the question in the caption above is New Smyrna (left) and Old Smyrna (right). Read on to see how the capitals of the columns indicate their age.

A Walk Through Smyrna

A tour of Smyrna must be done during the workday, as it is an active archaeological site. There are no ticket-takers (no admission charge either), and the times I have been there, I have observed diggers working along a wall or archaeologists in the courtyard next to the administration building piecing together pottery shards.

The tour starts at the top of the hill where the settlement lay. Today it is 300m inland from the Bay of Izmir. In ancient times, the hill would have been a peninsula, nearly surrounded by water.

Looking eastward, the slope falls away, showing a long, straight street — called “Athena Street” after the temple that abuts it on the east end. The first things one sees are the five capped pillars of the Temple of Athena, made of tufa stone — a composite limestone with visible grains of sand and shell. This is the earliest Greek temple found anywhere in Anatolia.

In the foreground are the outlines of city houses: each of them seven or eight rooms clustered around a small courtyard with a narrow passage to the street.

The closer one gets to the temple, the bigger the buildings get, and we find a Megaron a large chamber fit for a meeting room or throne, and behind it an architectural marvel of its day: a double megaron house with two stories, five adjoining rooms, and a front garden! (Remember, the earlier housing complexes on the site had separate rooms that opened onto a courtyard.) Dating to 650-600 BCE, it is “oldest known multiple-room, two-story house with one roof.” It may not seem like much today, but it classified as a “skyscraper” in its day, TWICE as high as any home in Smyrna — save the temple.

The temple sits atop a raised platform. Six pillars set in one corner of the complex have been restored. Most striking about them is their golden color — quite different from the marble columns of New Smyrna — as well as their capitals. The shapes of scrolls are evident, but these are not the flat scrolls of Ionic Columns of later centuries. They are taller, more erect, similar to the Papyrus Colums of Egypt.

The temple had a broad courtyard, and standing at the base of the columns, you can see chambers which must have once been underneath the paved platform. The broad steps leading from Athena Street up to the temple are barricaded by a wall of stone blocks — those weren’t left there by archaeologists. I’ll tell that story later.

Continuing past the temple on Athena Street, we leave Old Smyrna through the Eastern Gate. In ancient times, this led to a river quay. In later years, as the ground silted up, and the settlement spilled out beyond the city walls, temples and fountains were erected outside the city gate.

The Walls Come Down

Old Smyrna’s walls were a marvel of its age, but they came tumbling down.

Several times.

The first occurred in 700 BCE when an earthquake leveled the city. The ruined walls may have been still under construction when an Ionian army from Colophon attacked in 688 and incorporated Smyrna into the Ionian League of city-states that stretched along the Aegean south all the way to Miletus. The weakened Aeolian League continued north of the city.

Sixty miles (90km) to the east, a new kingdom arose. Around 700, the king Meles of Lydia founded a dynasty that would grow to one of the richest in the ancient world. Centered around the city of Sardis, the burgeoning empire would soon seek access to the sea, and Smyrna was the closest port.

(I pause here with an aside about Old Smyrna’s most famous son: the poet, Homer. Born in the mid-8th Century, he lived prior to the great earthquake and composed epics about the Greek invaders of olden times and their perilous odysseys home (The Iliad and The Odyssey). Some ancient sources give Homer the last name, “Melesigenes,” which means “born of Meles,” claiming he was born by the river of that name, which flows into the Bay of Izmir still today. To this I wonder: what if he was Asian, the son of the king of Lydia who had the same name?) This will call for another Substack on the subject soon, I promise.

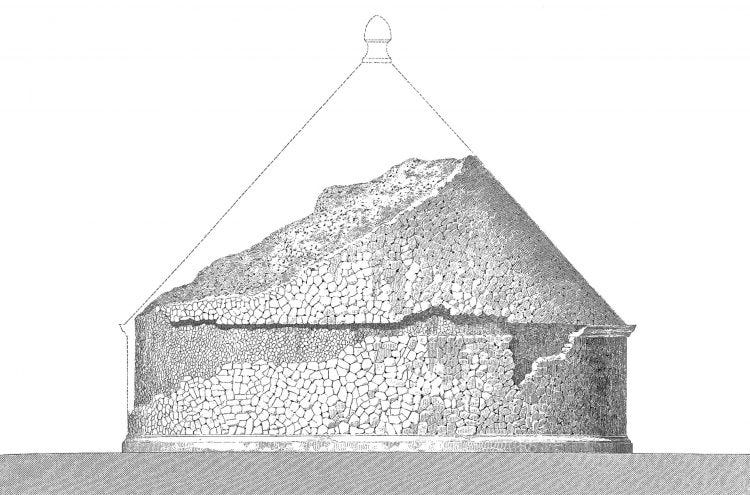

Lydian efforts to conquer Old Smyrna were rebuffed until 600, when the Lydian king, Alyattes built a huge siege mound on the north side of the wall and overran the city. I remember seeing the highest point of the hill — covered by trees today and unexcavated. I thought, “That must be the site of the acropolis or the theater,” structures which were usually built at the highest points of ancient cities. I now believe that it is Alyattes’ mound, towering over the ancient city still.

The city was sacked, its population ruined and driven away. The last effort to rebuild the temple occurred in 590. It was never completed.

That’s because Alyattes’ great-grandson, Croesus was conqured by Cyrus the Great of Persia in 547 at Sardis. After their victory, the Persians sacked many other city-states along the Aegean. In 545 they approached Sardis. The block wall that blocks the entrance to the temple was erected to block them — the Persians. (It didn’t.)

Its walls breached. Smyrna would never rebuild its skyscraper or temple. It remained a community — unfortified — for about 230 years until the founding of New Smyrna 10km to the south in the years after Alexander’s conquest.

By the time of Alexander, the silting of the Meles Delta had reached Old Smyrna and may have already left the city separated from the shoreline. Today the bay lies about 400 meters from the edge of Bayrakli Mound where the ancient city stood.

A Lost Wonder

One ‘tantalyzing’ site near Old Smyrna is lost to time, buried under the apartment blocks on the far hill. In ancient times, cemeteries always lay outside the city gates, often along a “Sacred Road” that led to a rural temple a few miles away. Across the ravine from the eastern gate, there was once a mound of earth atop a round base, lined with stones. This was known as the Tomb of Tantalus.

Tantalus was a legendery king who ruled the western slopes of Mount Spil, one of the two mountains that guard the eastern approach to Izmir. He is known to readers of Greek myth as the king with terrible judgment who invited the gods to feast on the meat of his son, Pelops, hoping to scorn them with his “big reveal” at the end of the meal.

Instead, the gods caught on — all but Demeter, who nibbled a piece of the boy’s shoulder. They resurrected Pelops and cursed Tantalus to a horrible fate. He would forever stay in one place in Hades, water up to his chin and delicious fruit hanging over his head. But if he stooped to quench his thirst or raised a hungry hand, it would disappear. Again and again and again. Forever.

His spirit may still be in Hades, craving food and water that are always out of reach, but his grave is gone.

Tantalus’ legend remains, and it is one of the fascinating things the visitor will find at Old Smyrna.

Old Smyrna/ Bayrakli Mound is quite far from the fascinating sites of Konak and Alsancak in central Izmir. But for history-hunters, it is one of the most fascinating places in the city, if not along the Aegean Coast — it predates Ephesus by two millennia.

The lack of weekend hours, and the fact that it is an ongoing dig site — oriented more towards professional archaeologists than casual tourists — really makes it cool.

Another, better-known migration was that of Hebrews, who Exodus occured during this era.

When Odysseus first lands on Ithaca, he tells the swineherd, Eummaeus the “Cretan Lie”: that he had gone to Egypt in search of plunder and almost lost his life. Modern scholars tie this to migrations that were happening at the time of Troy’s defeat, making this famous Lie more Truth than tales of Cyclopes, witches, and whirlpooles.

These facts come from Cumhur Tanriver’s SMYRNA Bayrakli Mound, a brochure given to me on my visit.